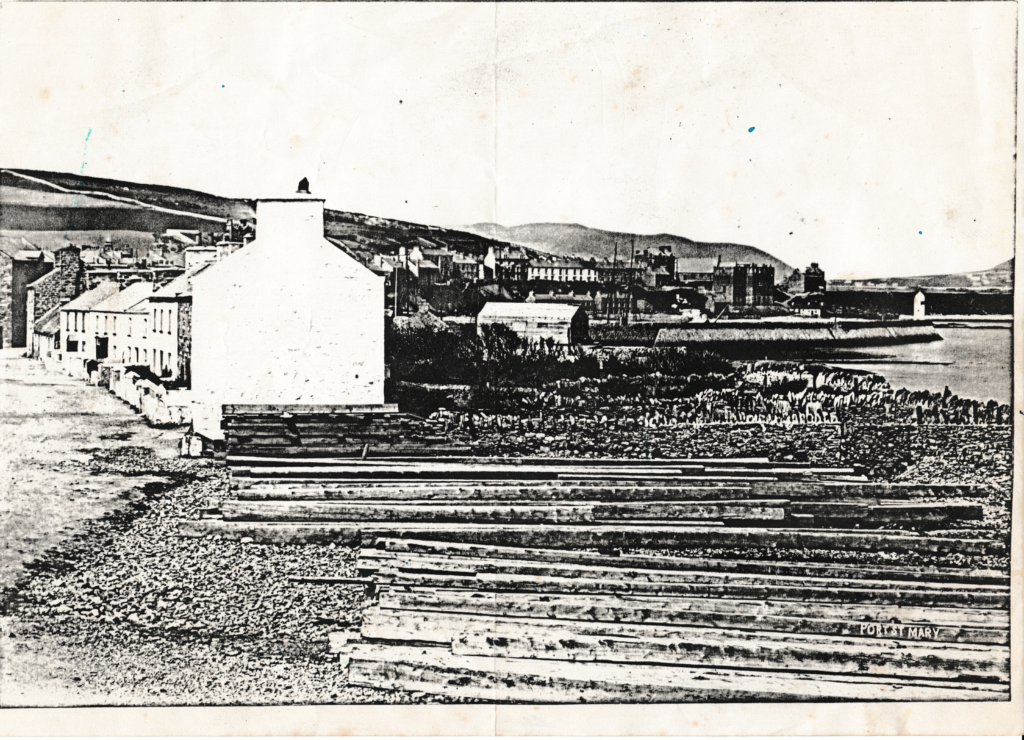

Robert Cain built Sheila in 1904, in his yard, on the beach of Port-St-Mary, Isle Of Man for a price of 100£.

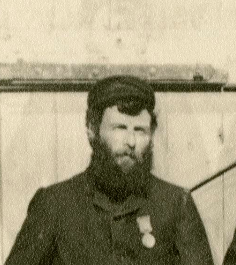

We have this picture of Robert Cain with an account of the event whereby a great snowstorm on 7 February 1895 made visibility impossible and resulted in the steamship Vigilant coming ashore in Carrick Bay, where her position was seen to be perilous. As there was no lifeboat stationed at Port St Mary a request was sent to Castletown but, as immediate help was required, the six men launched an open boat and rescued six crew from the Vigilant, landing safely at the Smelt. For this action the men were awarded the silver medal of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, and this picture was taken.

In 1902, Robert Cain finished Quest for Charles W. Anderton. Anderton (1866-1944) was an art student and sailing companion of both Albert Strange and Robert Groves. Quest was a 13T yawl of 36’ designed by Hamilton. Quest was later sold to John M Mc Ewan and renamed Fiona. She has been renovated and is sailing in the Netherlands. In 1907, before the beginning of his Summer cruise, Groves mentions that he visited Quest II in Tarbert.

In is likely that Adderton was an inspiration for Groves and introduced R. Cain to both Strange and Groves. But Robert Groves was already connected to Isle Of Man, where his family was spending the Summer month at Ramsey.

After Robert Cain finished Sheila in 1904, he proposed to work again for Albert Strange at the same price that he asked for Sheila. It is dubious whether a second Albert Strange yacht was built later by Cain, by the name of Sea Breeze, design #75, a different and slightly shorter yacht to Sheila.

The economics of building Sheila

Let us get into deeper into the economics of building Sheila.

Robert Cain built Sheila in 1904, in his yard, on the beach of Port-St-Mary, Isle Of Man for a price of 100£.

First question : was it cheap or expensive ?

100£ in 1905 would be 15.000£ today. Without VAT at the time, this would transform roughly into 18.000£ or 21.000 euros.

Cain was extremely price competitive for an aspiring yacht owner like Groves, operating on the Isle of Man, where the standard wage for an unmaried farm man was lower than 40£. This puts the price of Sheila in a different perspective : she was built for the value of 2,5 times basic minimal yearly wage. This would be more or less 50.000 euros after VAT in today value in Western European countries.

We can take a different perspective and look at the cost of living for someone living like Groves. 100£ would have been his yearly rent and taxes, or his budget for the family food, or his budget for dressing up. So more or less 15% of his annual income.

As a first conclusion, Sheila was built a at very competitive price, taking advantage of the cheap skilled labour available on Isle of Man. Groves was making a reasonable investment but not one that everybody could afford.

Second question : was Cain more competitive than Beneteau ?

We have been discussing a price of 100£ which in today’s money would equate to values between 21.000 and 50.000 euros.

As a comparison the catalog price for a new Beneteau First 24 starts at 66.000 euros. The discussion of the virtues and vices of modern mass production sailboat is not in the scope of this analysis. We chose the First 24 (ex Seascape 24) because it is a small, well designed cruiser which can compete in a club race. Like Sheila as the time, it is not meant to be a luxury item. But it is sold at a value which is basically more than a year of spending for 90% of the population in our Western European countries. The people who can affort one are also the well-off.

So can we conclude that Beneteau charges 50% more for a basic plastic boat than Cain used to charge for a wonderful work of art ?

Going back to economics, Beneteau chose to produce its First 24 in Slovenia – so they made a decision very comparable to Strange and Groves’.

Let us try to understand what Cain would charge today. Working as a shipwright was already meaning (and probably more than today) hard and long hours, recognized as skilled and valuable work, Like today, a shipwright would base his asking price on the number of hours of work needed to perform the job. He would also look at the cost of material, and we need to keep in mind that Sheila was not made with very fancy wood (at the time.) We do not have the hourly rate charged by Cain and the breakdown between hours and material. But we can try to understand what this hourly rate would be.

In 1905, carpenter were not the worst off, with wages of 32 shillings per week. This is 50% more than a labourer. Using this hourly rate (50% more than the hourly rate of a labourer), the price for Sheila would equate very roughly to 3.400 hours of work.

At today’s hourly rate for shipwrights (60 euros incl. VAT) the price for Sheila would be 200.000 euros if she was to be built again in Western Europe.

Today, at a 200.000 euros price, Cain would not be competitive at all.

He was able to charge very competitive prices at the time because he was taking advantage of cheap labour (like Beneteau today) but in 120 years productivity and innovations have changed the boat industry. Wooden boatbuilding is no longer as competitve as it was in 1905. Even with power tools and modern glues, carpenters who do custom work have not been able to increase their productivity as much as the other industries and as much as resins and other technologies have helped the boat industry improve its costs.

To finalize this discussion, more recently, wooden boats are not getting any cheaper. The hourly rate for a shipwright was 12£ in Woodbridge in the 90’s. Now it is 60£. This is not only the impact of inflation which would have made the 12£ become 24£. Shipwrights are increasing their rates to match their costs and to keep their purchasing power but since they are not making as much productiviy gains as other businesses, they are creating a cost differential between classic boats and standard boats which is increasing.

A solution for a number of classic boats builders or owners is to turn to lower wage countries with maritime tradition, like Groves and Strange did.

Another is for the guardians of these treasures to spend the hours themselves and combine their energy with that of the pros. I think many shipwrights are welcoming these newcomers to their yards and take pleasure in showing their skills and know-how to highly motivated and willing hands.