What is a Lady without a proper attire ? Sheila is starting her 120th year with a rather old kit :

- A main sail (150 sq’ in terylene – 1983) by Gayle Heard.

- A jib (85sq’. 2 reefs on a wooden pole roller system as invented in 1878 by Captain Edward Du Boulay) – 1997, same make as the main)

- A mizzen sail (75sq’ – by Sextant le Crouesty – Pascal Maurion – in colour “champagne”)

- A staysail or reacher meant to be set to the end of the bowsprit and sheeted to the boom end

- A spinnaker (200sq’ single luff set masthead, to the gamon-iron eye at stem-head, and with a 20’ pole.)

The only “new” sail is the mizzen. The staysail and the spinaker come extra as “racing sails”. Before I have new sails made for her, I want to understand in details the choices which have been tried and tested. In a snap :

- The Albert Strange design was for a cruiser, not a racer (and she should stay that way.)

- Sheila should be manageable single-handed under normal circumstances and by 3 people when driven to the max. In the specification published in the 1904 Humber Yawl Club Yearbook she was described as follows: ‘Although she will not often be sailed single-handed the sails have been kept small enough for easy working by one hand.’

- The current main sail is the best she has ever had (living human’s memory)

- The jib is deemed less critical but having a smaller jib was penalizing her performance and she should not be rigged as a cutter. Multiple jibs will not add performance on a such a small yacht. Sheila should not sport a flying jib. As she ever ?

- The mizzen is bigger than a typical yawl and key to the balance. It is rigged as a gunter rig.

- The main mast in one part is deemed original and no one wants to alter it. There are no spreaders, and no there is no extension.

- According to MB, a top sail was not part of the original sail plan and the mast is too short for it. Still, the most radical jackyard topsail was tried – with some limited success. See note (1)

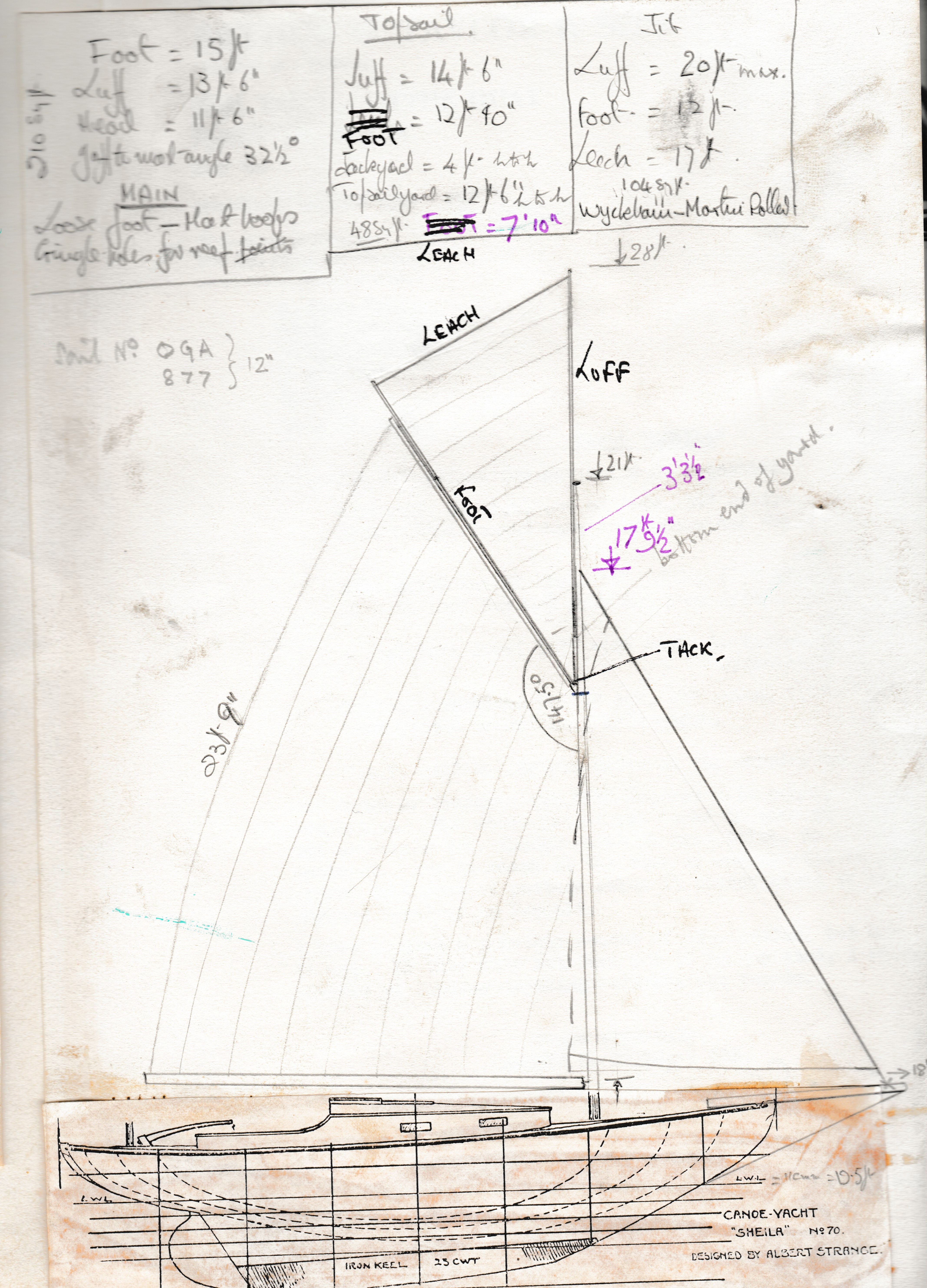

The sail plan designed by Albert Strange is lost.

Evolution of the sail plan

1906

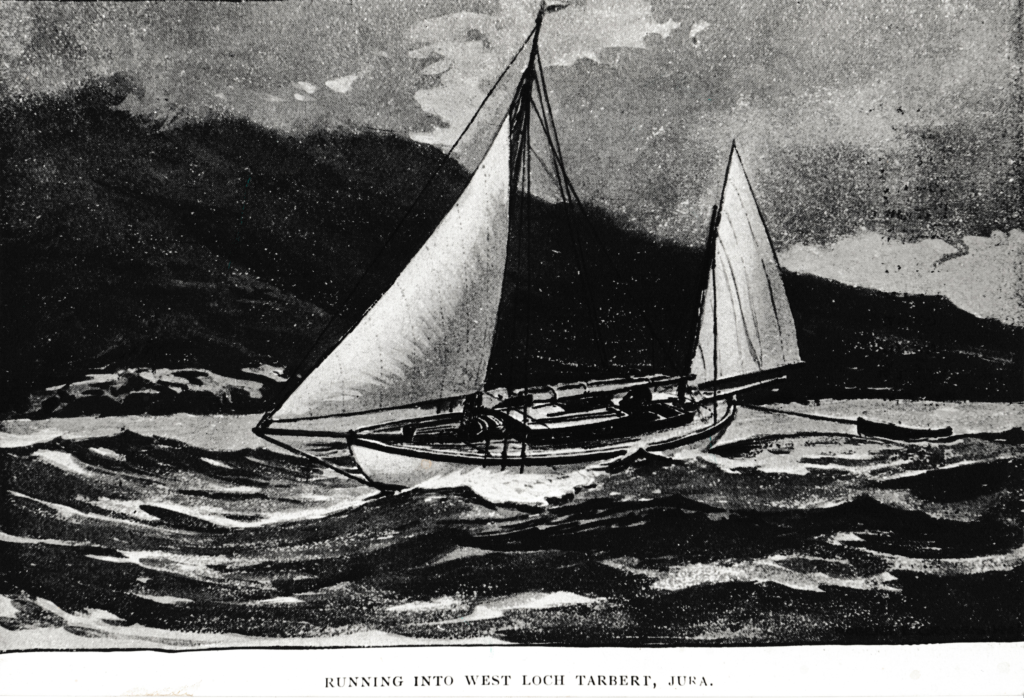

This water colour is very interesting, showing that in rough wind and sea conditions the boat was sailing as she is today with jib and mizzen. On this picture she carries her original sails that were made for her by R Cain.

The bow sprit was shorter. There is already a forestay in addition to the jib stay.

The main mast seems to be supported by three sets of shrouds on each side. We can speculate there is a pair of running backstays and a toping lift for the boom. There are no spreaders. The mizzen was already big and set up on a gunter rig. The mizzen mast is supported by a single pair of shrouds. The boat has navigation lights in the shrouds. The bumpkins seems to be pointing upwards.

Overall Sheila is incredibly similar to what she is today.

1907

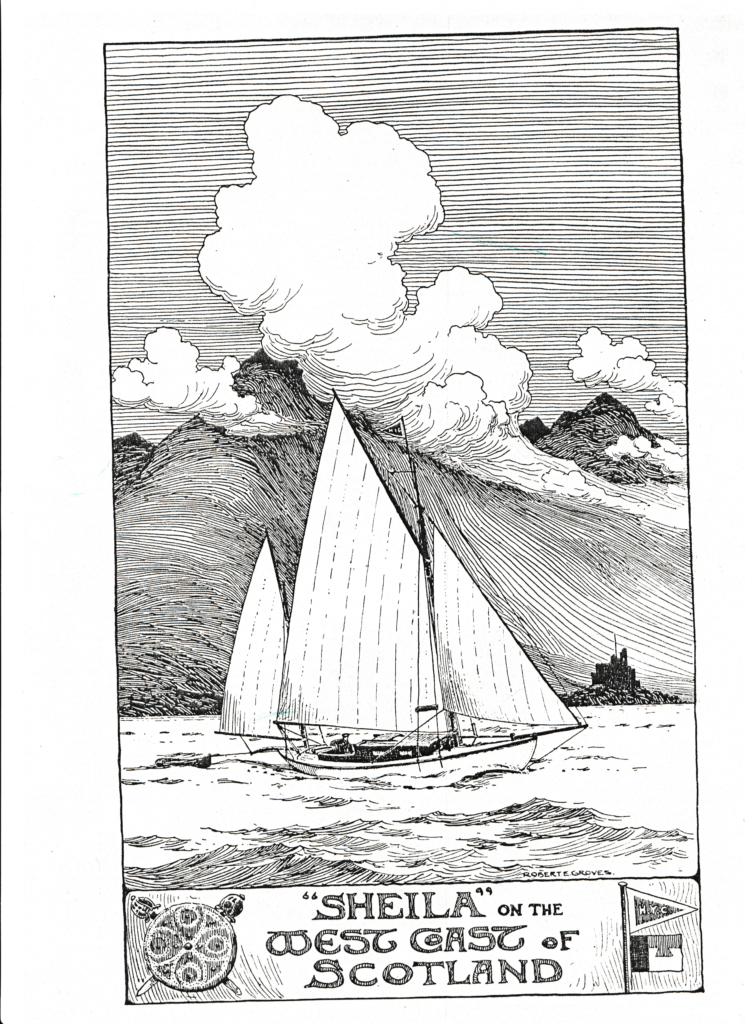

This drawing is not very detailed, but interestingly we can see that the bumpkin was already arched and not straight as represented in the 1906 drawing. The horse of the main sail is also very visible and similar. There are no running backstays and only two pairs of shrouds.

1908

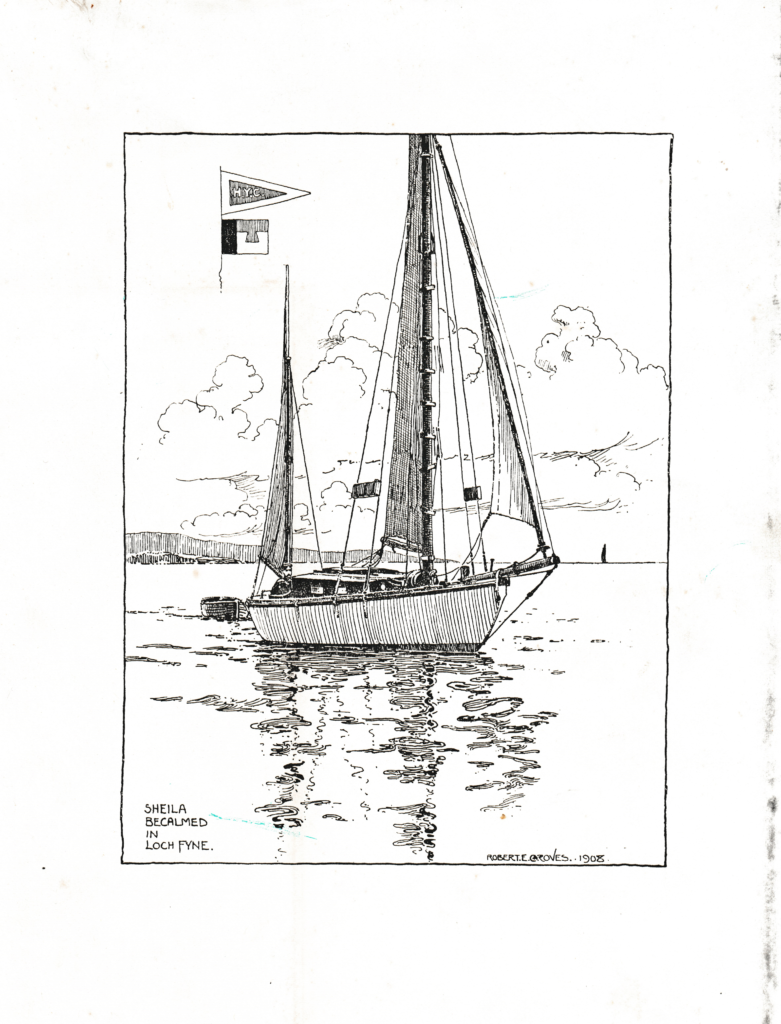

On this picture the furling jib is very visible. There is no stern-head forestay, easying the process of tacking. There are 3 pairs of shrouds and no running backstays. The mizzen is supported by a single pair.

The mainsail is set to the mast using mast loops. They were recreated during the 1979 restoration but today the sail is laced.

As a side note, the two pennants pictured on the top left include Groves’ « distinguishing flag » for Sheila, as registered with Lloyd’s in 1908.

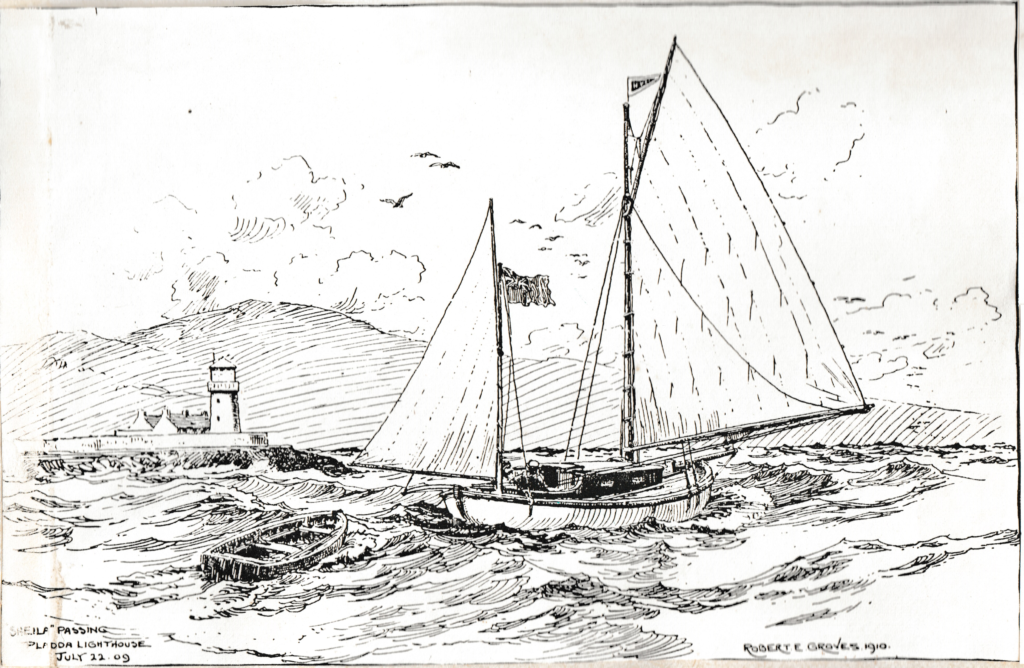

1909

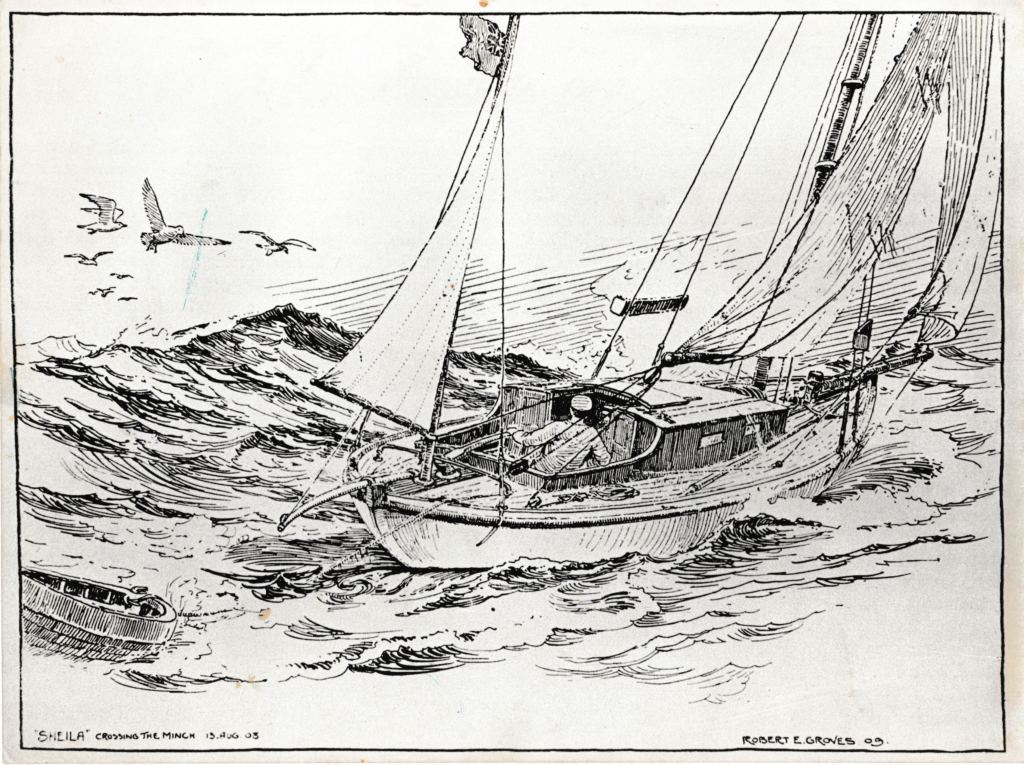

On the first picture, we see that the jib sheet runs through a block or a deck fairlead before going through the coaming of the cockpit. The setup for the main sheet goes through more blocks than today.

Here we can see that three reefs were available in the main. The running backstays are not visible. We can rule them out. We can also rule out the 3rd pair of shrouds.

1911

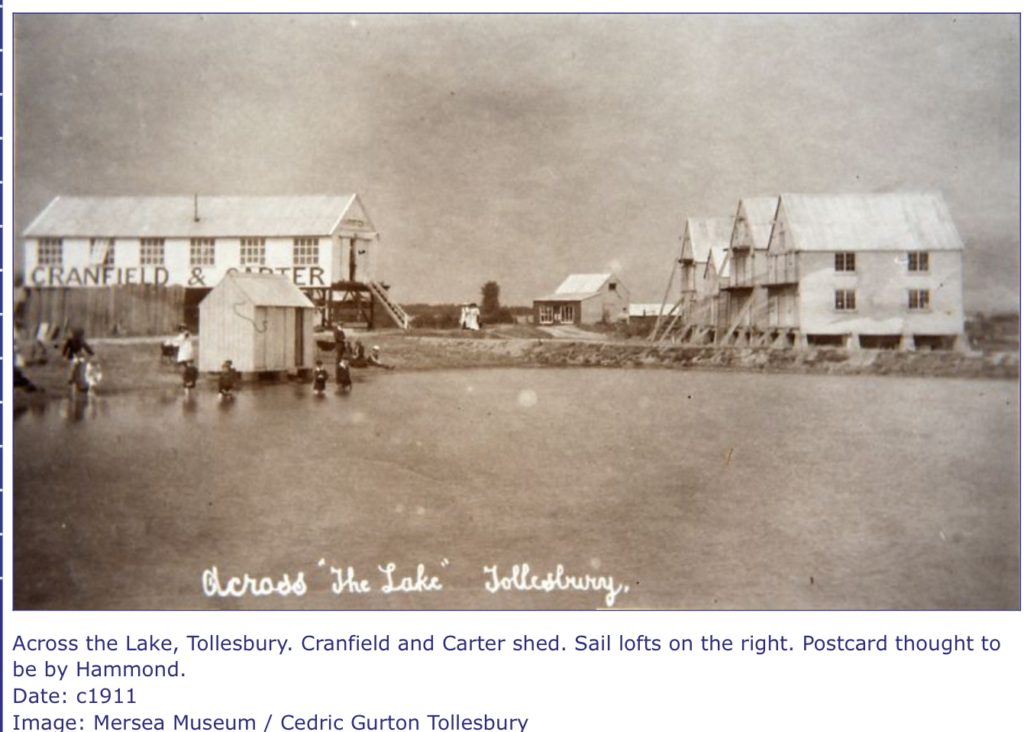

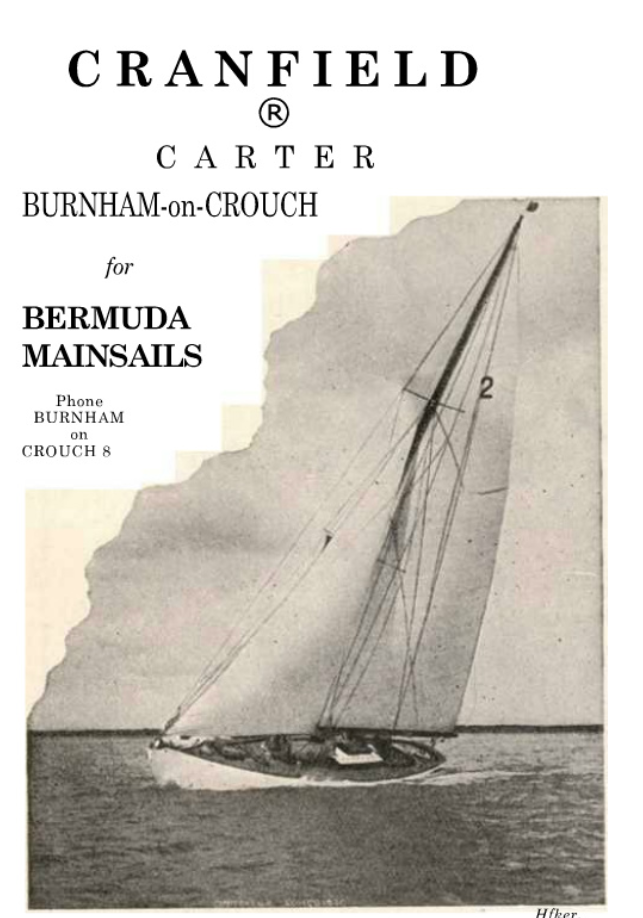

This picture is very interesting in detailing the sails. In 1911, Sheila does not sport her original R Cain coton sails. Her new sails from 1910 are from the loft of Cranfield&Carter of Tollesbury.

Today Sheila has a mitre cut main sail. In 1911, the jib was mitre cut but the main and the mizzen were made with panels parallel to the leech.

We seem to see 4 battens in the main, which are probably reinforcements only. The mast loops seem to be replaced with lacing.

Sheila is flying the club flag of the Royal Irish Yacht Club.

In 1914, when she was rebuilt, Cranfield&Carter made a new kit. She was still wearing them in 1921.

In 1923 a new set of Perry sails were made, that she was carrying in 1925. And in 1932 she was sporting new Perry sails again. In 1937 she got a another set from Cranfield&Carter but in 1956 she was still registered as using her 1932 Perry kit. In 1937, her new outfit was from Cranfield again.

1938

According to JY Wilson, Sheila had a trisail gaff, last used in 1938.

“Pre-war she had a very neat loose footed gaff trisail. That sail and the rest of her outfit (Cranfield and Carter best – really best Egyptian – here were cheaper cotton samples quoted – and used only two seasons before the war) were never found after the fire at Ayr about 1942. I came accros the gaff when rooting among the multifarious stuff stowed in the garage rafters just before Christmas. “

1946

In 1946 she had new sails by Greenock Tent & Sails. They were changed in 1957 (Leitch of Tarbert) and 1960 (Jeckells of Wroxham.)

1970

Sheila on the 4th of July 1970, on passage to Lochaline. JY Wilson & GD Stewart. The mast is rigged with spreaders. The spreaders have probably been added during the 1914 refit. They were maintained until the 1990’s. The main sail is smaller than the original design and in terylene. JY Wilson was a tall man and getting old, he was not ready to deal with the low boom that Sheila sports.

1978 and 1979

In 1978, Mike created a sail plan for Sheila based on his understanding of Strange’s design (including the sail plan of Mist), the many drawings and pictures from Groves, and the record of the alterations that had been made by the previous owners to accomodate for their own preferences. Mike’s objective was to be the closest to the original rig and sail plan and to add a topsail.

Mike ordrered a new set of sails to replace the smaller terylene main and return Sheila to her historic beauty.

To have an 2024 estimate of the 1979 cost you can safely multiply by 7, and VAT was 12,5%.

1980

This is Sheila after her 1979 refit, sporting her Arthur Taylor cotton sails.

1982

The main sail has the same cut as in 1911 (but without battens ?) with 2 rather than 2 reefs. It was coton again until it was changed to the mitre cut polyester sail end of 1983.

Sheila has a shorter bowsprit than today.

It is difficult to understand what is going on at the bow. Potentially, the sequel of a spinnaker launch ?

Sheila sports a very aggressive top sail on a mast extension. At her scale, this a real “jackyard topsail” ie “the sail with murder on its mind.” There is a mast extension and a gaff extension (although the latter does not extend much.) A very pretty sight !

Remaining from this period is the little sheave at the top of the gaff for the topsail sheet.

1983

Sheila is at the left (at the right is Eel, a 1895 George Holmes design.)

The main mast is sporting spreaders, two pairs of shrouds and running backstays.

We cannot see the bowsprit which was extended in 78/80 and then changed in 1987 when it broke.

Here we can see her again racing in 1983.

Sheila sports an asymetrical spinnaker on a port tack. There is something mysterious at the top of the main mast. Maybe the spinaker is hoisted at the level of the jib and not at the top of the mast or what we see is an extension. There is a square mark at the foot of the sail.

We cannot see the spinnaker tackline and the spinnaker seems to be set at the end of the bowsprit but maybe there is a small jockey pole on starboard which would still be onboard. The sheet at port is pushed outward by a two parts spinnaker pole which is still onboard as well. This spinaker pole is supported by a topping lift.

Sheila also sports a surprising mizzen staysail. It seems to be tacked on the shroud aft and sheeted at a leeward point at the bow which is possibly the shroud of the mizzen mast. This is a challenging setup for a jibe or a tack, but is potentially adding to the performance. Mike indicates in his notes that this setup made use of the Arthur Taylor cotton jib of 1979.

On this picture (unknown date but same era) we see different details and a different setup. The sails are probably the same.

The jib has been furled and the boat is closer hawled.

The spinaker is not hoisted at the top of the mast, it is hoisted at the level of the jib stay so that the pull is rightly compensated by the running backstays. We seem to see that the square patch on the foot of the sail is now on the luff side. Maybe the spinnaker has been rotated to accomodate for the difference is height.

The spinnaker is tacked at the end of the boom. The spinaker pole / jockey pole are not used.

The mizzen stay sail is set on the mizzen mast – quite low on such a gunther rig. The sheet seems to be tacked at the very bow or at the end of the mizzen boom (?)

In 1983, after this picture, Sheila got a better Gayle Heard set of sails that she still sports today.

1990

This is Sheila with the Gayle Heard main sail she sports today.

The jib sheet goes through a fairelead as it did in 1909. The jib was chainge in 1998.

The bowsprit which was broken and changed in 1987 is definitely much longer and is the current one.

Sheila is sporting the pennant of the Old Gaffers Association.

1995

A new mizzen and a new furling staysail were made by Heard – along with a sailcover.

1996

The mast extension seems to be present (but maybe it is just for a bungee.) Still there is no longer a topsail on the pictures.

The furling system is different than today and not very “period”

1997

The jib was changed to another new Heard & Clateworthy, with a different cut. The fairleads were not needed anymore.

2005

Same sails (perfect trim) – the spreaders are clearly gone, for good. The forestay compensates the action of the peak halyard. The sheets of the jib go directly to a cleat inside the cockpit (there is no fairlead) The furling system is the one Sheila has today.

2 details in 2005 : the shrouds are adjustable with deadeyes. The mast coat is a different concept.

The mizzen is supported by two pairs of shrouds now.

(1) Mike’s notes on Sheila’s topsail (1999 ASA Yearbook)

Topsails are fun, topsails are photogenic and topsails definitely do make your gaff yacht go faster – but those wonderful acres of faultless canvas seen spread on the great racers of the past were not achieved without a great deal of inherited skill and effort. The effort we can still apply but much of the skill has been lost, a little of which I have re-learnt the hard way by setting a topsail on Sheila’s rig, which has contributed to the trophy cabinet noticeably. .

If a topsail will not drive the boat to windward, and is a pig to set and hand, then the effort in its creation is wasted so let us examine what factors achieve this. First the sail must be cut flat enough to set hard on the wind. Like a mizzen this is actually flatter than most sailmakers really like, but insist, or the thing will flutter at the luff and head when driving the yacht to weather. It must stand well. This is achieved by proper control of all its edges, which must be rigged so that they can be kept board tight; this means a great deal of well thought out string!

It is vital to recognise that the arrangement we create be really easy to hand in a sudden squall for a big yard topsail jammed can begin a series of cascading calamities that may end in considerable danger. So, while the design of it and its gear is being considered, give more cam to getting it down quickly and surely than to getting it up. For this tactically placed downhauls are vital for it will not tend to fall down of its own. Have a downhaul on the heel of the yard for this purpose as well as the one on tack of the sail used for straightening the foot when set. If you are using a `club’ or `jackyard’ then it is essential that its bottom end extends below any gaff – span or parts of the peak lift as if not that end will poke its way through such rigging and jam the whole show solid. A longer club rather than short is good here – examine the photographs of late 19th C racers and you will see that they have solved this jamming problem with really long clubs, which also have the advantage of setting the foot tight on a spar rather than having to rely on the sheet.

My preferred term for the little stick on the foot (the edge that runs down the gaff of the sail is `club’ (a spar used to control the foot of a sail as in `clubbed jib’ for a self tacking jib) which was in common parlance on the Clyde at the turn of the century; weather suitable for the setting of those majestic creations was called “Club Topsail Weather” – end of hobby horse! When arranging the sheet, the rope that pulls the club or clew out to the gaff, its position relative to the sail and the gaff is important as if it is pulling from the wrong angle the sail simply will not set flat enough all along its length; the sheet has to pull two parts of the sail tight at once, the foot and the head. It is for this reason that a club is useful as the position of the sheet on the sail can be altered by moving it along the club till the optimum setting position, that pulls the head and foot tight equally, is found. On this subject of setting when you have achieved a perfect set with all the rope hauls in their right positions on the spars, then either mark that position or better still mount little wooden thumbs to anchor the rope from moving along the relevant spars.

If you are only attempting a jib-headed topsail without spar then its setting is relatively easy – but the joy of topsails is only fully achieved by getting the head of the sail well above the top of the mast and out beyond the gaff. For this you need a Topsail Yard, on which to set the luff and a Club on which to set the foot. The main desideratum for the yard is lightness with adequate stiffness to avoid it bending away to leeward in a puff, and allowing the head to flap. For this take a little trouble in its making bearing in mind the `bending moments’ to which it is subjected – so make it thickest at the hoist point, tapered from here in both directions to truck and heel. This design also allows room to drive a hole through, at the hoist point, to take the halyard through the spar which is also aimed at achieving closeness to the mast when hoisted. Ideally, if you have enough mast height, try to have the yard arranged so that it balances on the halyard hanging the right way up – Sheila’s mast is so short that hers is heavily overbalanced which causes far more effort in setting and handing.

You will need to cut a proper sheave in the very top of the mast to draw the spar close to the mast – a strop and block will allow it to flail about too much; all that stuff flailing about that high is terrifying and causes much damage. Ideally create a chock on the after side of the mast for the spar to be pulled into at the hoist; control of the hoist point goes a long way to achieving control of the other parts of the sail as this is the main anchor point. The position of the hoist on the spar, and as a result on the sail, is the determinant of exactly where the sail sits in the triangle created by the masthead and the gaff; experience tells me that it never is where you thought the drawing showed it and experiment will be the order of the day so set nothing in concrete till all is proved perfect. I have found that trying to get the heel of the yard to sit also in a chock situated on the aft side of the mast, to ensure perfect verticality, is the dream of engineers. Sailors use a hefty downhaul on the sail tack and a control line on the yard heel. In this regard the sail should extend below the bottom of the yard to allow of the luff being tensioned separately to the control of the spar with a big downhaul.

I achieve control of the heel of the spar by having a bottom haul that passes through a bronze loop mounted on the top face of the gaff jaws – the yard heel lying just above these. This loop is set back up the jaws a bit to pull the heel a little aft and set a bend into the yard to pre-load it somewhat against the sailing forces. I have arranged this line so that

when taking the spar down pulling this rope also dismounts the spar from the gaff to allow it to slide downwards easily. I do this by having a continuous circular line with a big knot in it, about a foot from the end, that passes through the heel of the yard, one side falling down one side of the mainsail the other down the other. When hoisting the yard the knotted end of this line is passed through the heel of the yard and tied to the other end of the line so that the heel is trapped between two knots, this allow the yard heel to be controlled from both sides of the sail – to haul it in to the gaff jaws and to clear it from the jaws for handing.

As you will begin to see string is at a premium, and we have not started on the sheet yet, so immense care as to fair leads for the rope runs and adequate places to make them all fast is essential. For this latter you

will need to set new cleats for handling all the extra ropes for bundling them on top of others will cause trauma when handing the equipment.

We now have a halyard, a heel control line and a downhaul just to control the fore edge of the sail and its yard. We now need a sheet. This can be really quite small stuff, indeed if it is thick you will get in all sorts of trouble as it has to perform some intricate turns; Sheila’s is only 5 mm nylon. It starts life on a cleat on the boom by the gooseneck, the hauling or `fast’ end, it runs up to an eye (or for bigger yachts a block on a floating strop) set under the gaff jaws and travels up under the gaff to a small sheave set in the gaff end. It then runs over the gaff, down to a cleat on the other side of the boom, the loose end that is tied to the club or clew of the sail. Because this line can get into all sorts of tangles on a small yacht I don’t reeve it at all unless I think it is topsail weather. As mentioned earlier the exact position of the sheeted end on the club will need to be experimented with – it must pull the foot really tight or the whole drive of the sail disappears; a slight curve in the head is permissible.

Setting the affair is a rigmarole that requires plenty of sea room until the order of activities and the correct leads for all the ropes, is established and learnt for tangles can cause real horrors. My dance goes something like this. Sheila’s topsail is permanently made up to the yard and club, all rolled up tightly together and kept in a tight fitting canvas `johnnie’ which is stored up one of the main shrouds.

1. Set the yacht sailing on the tack that allows the topsail to hoist in the lee of the main as it lies away from the mainsail and gets tangled up less.

2. Get sail and yard out of `johnnie’ lying along the deck, heel facing forwards with the halyard point close to the mast. Have it on the side of the deck on which the sheet fall is on the mainsail – for my method the lee

side. There are differing views on this question of lee or windward side but try for yourself

3. Make fast halyard to spar. If it is not going through the spar but round it stopped by a thumb then I have found that a clove hitch is effective though purists will use a rolling hitch; Ashley records a “Topsail Yard Hitch” but I have always found that the secret of knots is making the ones you practise often work well and no-body I know sets a topsail yard often enough to remember such esoteric stuff.

4. Make fast sheet to club. It essential here to decide a protocol for whether the sail and yard are going up outside or inside the topping lifts and to ensure that all the rope leads reflect this. I prefer using the inside as when taking the yard down the topping lift will help prevent it from falling over the side. The greatest grief with topsails occurs from not getting the leads for all the ropes right; it is this that requires the greatest familiarity if life with your topsail is to be one of harmony.

5. Hoist spar slowly on halyard while taking up the slack of the sheet as the sail rises. The trick here is to prevent the sheet getting itself round the wrong side of the club or tucked under an end or managing

loop knots round the topping lifts. I have the added delight of keeping tension on the sail downhaul to prevent the yard capsizing as it rises!

6. When heel of yard is level with hands feed the control line through it and join it to the end from the other side of the sail running from under the boom to complete the loop control line.

7. Drive the yard tightly up to its topmost point and belay the halyard.

8. Take the right end of the heel control line and drive the yard heel tight into the gaff jaws and make fast the line.

9. Set the Iufh tight with the tack downhaul and make fast.

10. Praying that in the interim the sheet has not got caught round the club or the end of the gaff haul it tight – it will need to be really tight to set the foot snugly along the gaff. Make it fast and make up the considerable length of fall that results to the cleat on the boom – surprisingly large cleats are required for this.

Essentially there you are and once the dance routine is learnt faultlessly it represents another personal skill that sets you apart from the plastic Bermudan brigade. It can be done by one! Sit back and quaff a beer as the cameras come out and you sail past the competition, but be mindful of the routine for handing it…

1. Set the yacht on a tack so that the topsail will come down on the windward side of the main. This seems illogical but works well because the sail drops better lying in the curve of the mainsail and can quickly be cleared by laying the whole gear along the boom and tying it with sail ties leaving all the string in place to be cleared later if the weather does not allow the sail to be set again.

2. Free the sheet enough to take the wind out of the sail and for the head to drop but not enough for the club and clew to flail around and get tangled up with the gaff hoists or span.

3. Free the halyard and, using the other end of the heel control line disengage the heel of the yard from the gaff jaws and clear the heel to drop past the gaff.

4. Using the heel control line pull the yard down while letting the yard head fall down towards the aft of the boat controlled by the topping lift from falling over the side – slacking and controlling the club with the sheet as you go.

5. Lay the whole shebang along the boom and make fast with sail ties.

If all goes well this can be done surprisingly quickly once all the falls have been made free of their anchorages. Since it is this that predicates the speed and ease of handing your topsail give the places and making up of all the falls the greatest thought or birds nests of the most spectacular sort result and swearing echoes across the oceans. As they say in today’s vernacular “Enjoy your Topsail”.

More about topsails…

(2) Mike’s notes on the reaching staysail : It is sheeted to the boom end. I think they have gone now but we had two permanently running ‘sheets’ through blocks on the boom end cleated to two cleats on the forward end of the boom, It’s foot was set to a running line out to the bowsprit end then its clew clipped to the end of the relevant running line then sheeted home – it was an enormously powerful sail which, of course trimmed with the main-sheet. and a spinnaker.

(3) Mike’s notes on the spinnaker : it was cut by one the great pre-war aces whom I knew. it was cut properly ‘Single luff’ so set to a 20ft pole – which should be under the stbd side-deck. It was made up of a wooden pole with a jaw at the end to rest on the mast so used to boom-out the standard ji then an aluminium extension with the sheet to a block at its end with a topping lift when (I think) went to the last=head. 1) Set Spinnaker-Boom, cleating its sheet on the main=boom horse. 2) draw foot of spinnajker out to bowsprit end, 3) clip sheet from the pole on to the clew of the spinnaker 4) clip halyard on to head and briskly hoist while also hauling out sheet. Actually very simple once one had got the technique in practice which won us a number of races while being invaluable in down-wind light airs when running back home up the Essex coast. It can all be done by The Crew of one.