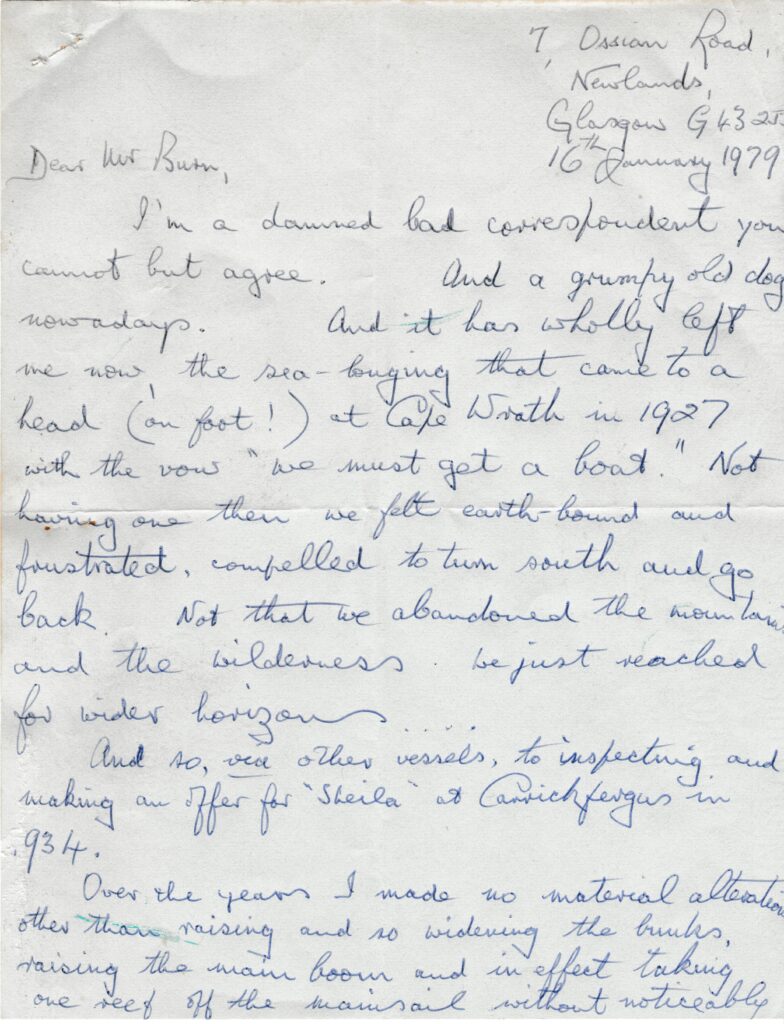

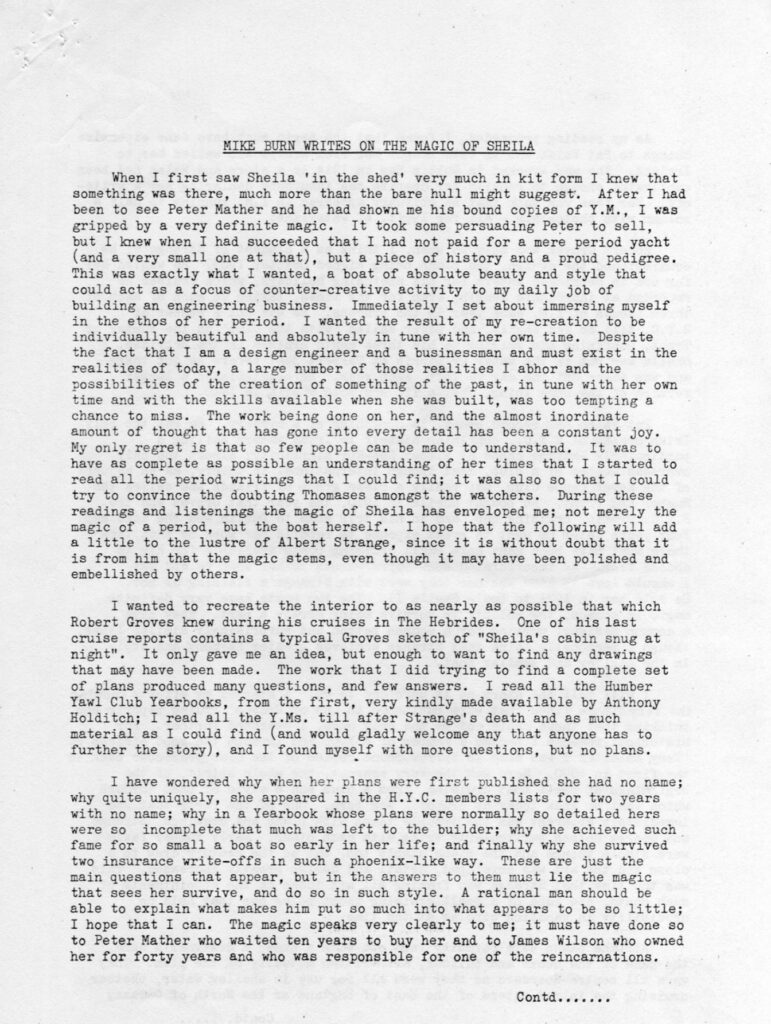

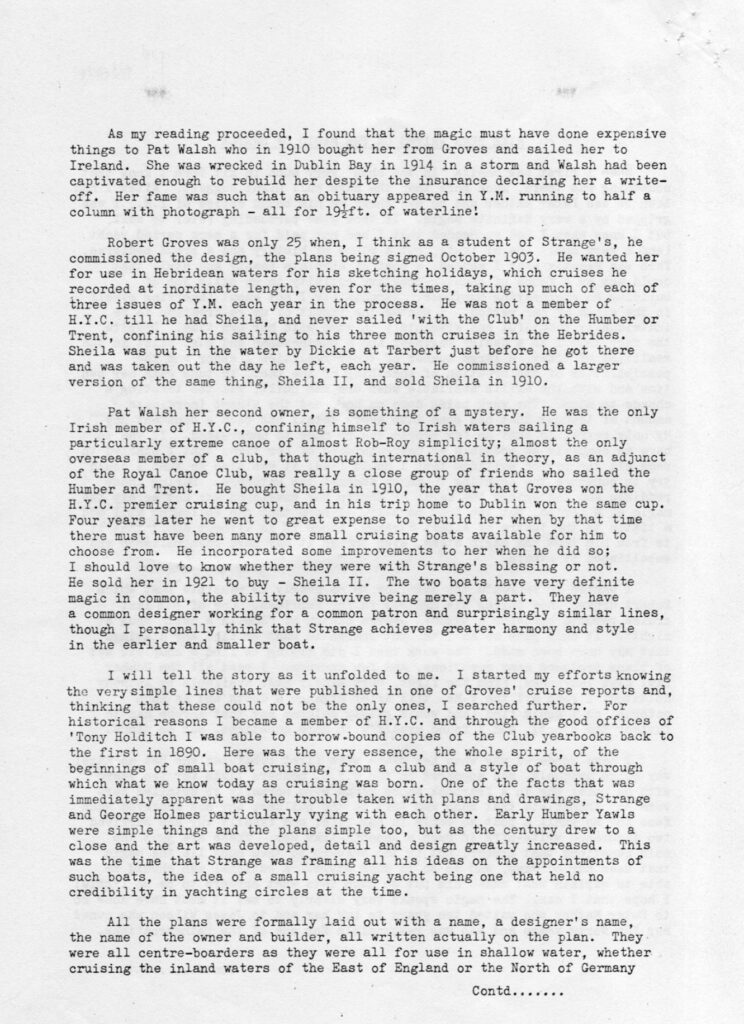

A letter from JY Wilson

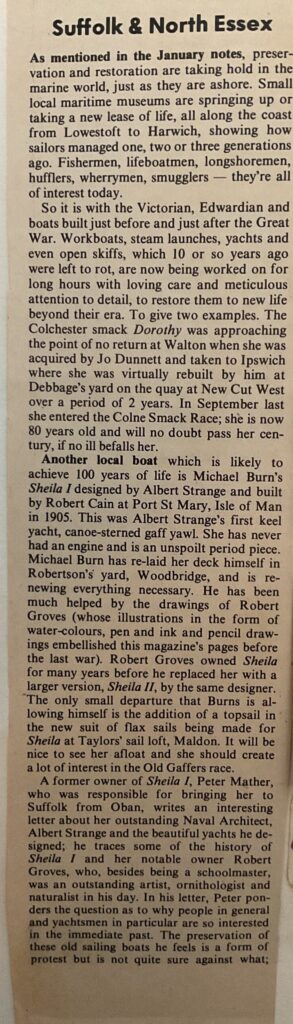

In “Yachting Monthly”

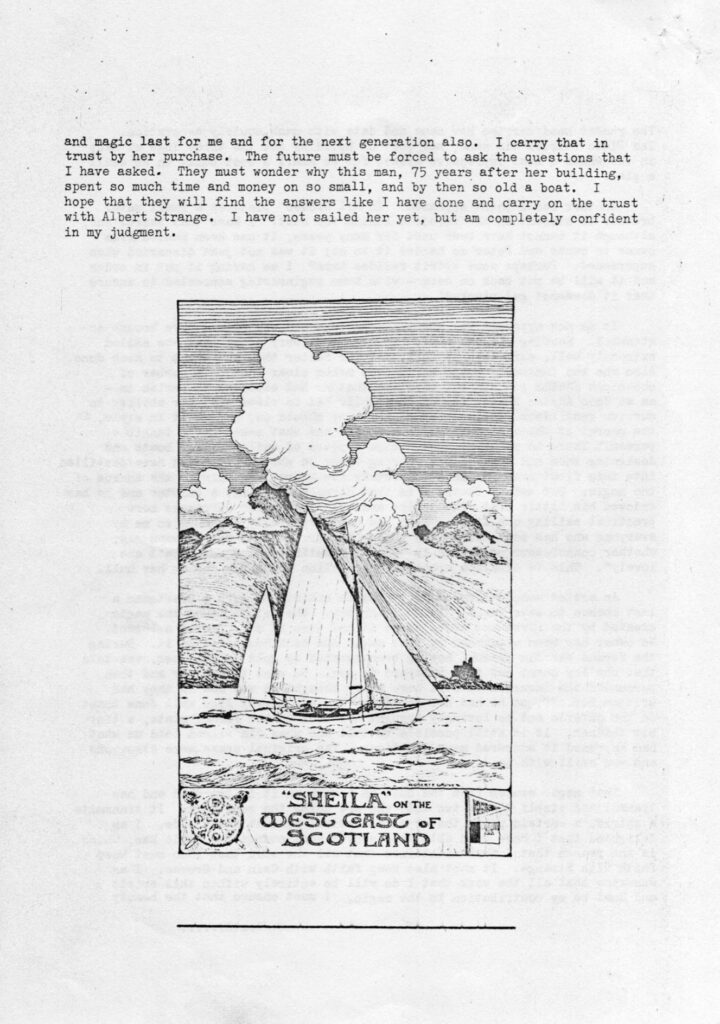

Sheila

A Trust Maintained

by Michael Burn

This is the narrative written by Michael Burn of the extensive refit Sheila received for her 75th birthday. It was made for the record and published in the Old Gaffers Association yearbook. This record is extremely valuable for maintenance and thus it is being translated in French.

For those members who were brave enough to read, last year, the reasons that I gave for the extensive restoration of Sheila I write this year to tell in detail what has been done, why, and what learnt so far. It is, necessarily, a long document, and even so not complete, but I fancy that an exercise of this nature is unlikely to be done again and, since Sheila is what she is, I think that it is worthwhile to make a record. Like any old artifact of value she had, naturally, been adapted to the needs and fashions of the period and, indeed, so it should be. My efforts, though, have been directed towards a removal of the veneer of time to examine the original conception. Particularly has this been done to see whether Strange’s writings and claims would be borne out in practice since those virtues he claimed seemed to me to be uniquely worth searching for. It is to Strange’s credit, and much to Jim Wilson’s, that his original receipt was largely unchanged when I found her, but many small differences were obvious. From my Vintage motoring days I know, absolutely, that there is no merit whatever in having a period piece hitted out with modern improvements. The full flavour of the period is lost and the advantages of time are not achieved. This, I fully realise, is highly contentious but I have proved my point so successfully with cars and now with Sheila that I am unafraid to maintain it. The corollory of the above is that not only should the details of the artifact be recreated exactly but that they should be recreated with the methods of the time and the materials of the period. The reasons are the philosophical ones stated above added to a very practical one. A mixture of techniques of different ages for the solution of restoration problems usually suffers from the “new wines in old bottles” syndrome. This ideal only slipped once or twice and the slips do not bear on the result in any material way. Also, important points of original construction can be missed or major troubles actually designed into a restoration by failing to understand and re-employ an original design or construction solution. It is for these reasons that Sheila’s restoration has been so ‘complete’ and so appallingly expensive. So much that was there and ‘would have done’ was scrapped in a ruthless search for exactly what Strange created. It is fair to say, also, that being what she is and it being her 75th birthday, many things, though in the character and quality of the time, were done to a higher standard than, perhaps, she saw originally, though the only item that really cost money here was the building of a perfect new clinker dinghy.

The first serious exercise was to put the keel back on. Here were the first ethical problems. Should I put back the 5″ filler piece that was probably added in 1914 to increase her draught or should I leave her exactly as drawn. Pat Walsh, who most certainly did it, knew Strange well and, quite probably, had his agreement when Sheila was rebuilt. On the East coast where 5″ is critically important my decision was complicated, “to leave out or replace” Hallowed by time I reckon that Walsh knew what he was doing and it went back in; so she now draws 3′ 10″. Also, should I go to fantastic lengths to find suitable ‘Lowmore’ iron and have the heel-bolts forged or use the correct Admiralty approved Stainless Steel. As an engineer I knew the chances of finding iron of a high enough quality were remote and I could make perfect ones to the highest standards in my own works. This was almost the only point at which a material other than that available at the time was used. The bolts had large, flared heads driven up into the iron keel in tapered holes and were nutted down onto the hog with large bronze nuts. Thick ‘Acetal’ conical washers were placed between the iron and steel for electrical insulation. EN-58 was used for the bolts the only stainless suitable for the anaerobic conditions of keel bolts and the only real possible trouble spot is the nuts but every one is very accessible (stainless nuts seize to stainless bolts!). The whole affair went together beautifully and since no attention was required in nearby areas job ‘2’ was tackled with much more enthusiasm; she looked much better with the keel on.

The next activity, which I set about alone, was certainly the most contentious in the eyes of friends and certainly the most soul searching. It was a considerable mercy that it was done so early or I might not have had the heart to do it at all. I wanted to recreate the original deck exactly and since the problem was so considerable it formed the corner stone of the ideas behind the whole affair.

It very neatly pointed the new wine and old bottles lesson and served, also, to make clear to those around that something slightly different was being undertaken.

A surprising number of ‘Jonahs’ appeared at this point, most people thinking, and saying, that I was mad. Since all I had to work with was a tatty, bare hull and dreams it was a grisly affair, only possible because the yard gave me a key to the shed for my personal use. Many Saturday and Sunday afternoons were spent bent double raking out the old seams and considering Albert Strange.

The reason for doing the job correctly was mainly structural, though philosophy and vanity entered into it. The decks of yachts of this period (and certainly Sheila’s) were integral structures with the hull and the term marine glue is used correctly since it is vitally necessary that the deck planks are glued together to form a structural whole with the hull. Merely squirting a sealer down is not enough. The solution of covering it over with something else adds weight and worse produces the “where is the leak” problem. One great advantage of a plain laid deck is that where the water comes in, there is the leak and it is easily stopped. As everyone knows a covered deck that leaks is worse than three dimensional noughts and crosses. Sheila’s deck is one of those super ones where the planks are bard and curved with the covering board let into the kingplank, so it is really smart and proves to be an enduring delight to the eye. Work started by making a special set of rakes. This was necessary since the grooves were only 1/8th inch wide tapering down the groove till the planks touched. It was necessary to remove all trace of the old gunges (the decks had been under canvas for 40 years) and to regenerate the sides of the grooves to virgin wood so that the new marine glue would stick. Jeffries No.1 marine. glue is still available. The rakes, after some experiment, were made from old files very carefully ground into the exact shape of the groove, finely finished with a sharp forward edge and after finishing rehardened. There was over 600 ft. of groove and countless secret fastenings to negotiate. The Kauri pine proved extremely abrasive and I became expert in regrinding the rakes to the perfect angles, not to mention the carefully ground old hacksaw blades, needed to remove the actual caulking from the bottom of the groove. I must have got through dozens of these alone and progress to a perfectly prepared groove was about 4 ft. an hour, all spent doubled on hands and knees using two hands on the rakes. It was a stupendous caper and nothing looked any different for the effort when all was done except that the grooves were covered with sticky tape to keep out the dust of later work.

It was intended that the ‘paying’ be done just before she was finally put in the water since it was expected that the whole restoration would take at least another year and a half, during which time the hull was going to dry out further and the deck seams would open up. If the deck were to be payed early on I supposed that when it opened further the gap so produced would place intolerable stress on the glue in tension. Although Jeffries No.1 is intended to be quite flexible this seemed to be asking it to do too much, It was planned that she would spend some time in the water before final work was done so that jobs of this nature would not be done with really gaping seams.

Although the paying was done much later on, its description follows logically here. It was done at a time when money and time were running out and was obviously going to be the one activity with the most risk as no-one had had experience of doing it in this material. It proved to be the one point where I very nearly lost faith as, although I had asked Jeffries for as many hints as possible, the gap between theory and practice was profound. The glue needs to be runny enough to flow down the thin groove yet it must not be too hot or it dries hard and is useless. The first two days’ attempts just had to be raked out again and spirits sank. Heads wagged and much ‘I told you so-ing’ went on. I asked one of the more mature men in a rival yard, who, with great kindness, came to help. It is well worth remarking here that one of the greatest rewards of the whole restoration has been the cooperation, understanding and help I have received from so many people during the job. The reactions of people to her restoration have provided me with an infallible guide and division between the real and the bogus. In this part of the world many really love old boats and will go to endless trouble to help those who are trying preserve them. The deck problem was an excellent case in point. The only thing that mattered was the problem in hand, not who benefited or who was going to charge who. It was clearly understood that the beneficiary was the boat herself, from and so she is; also one benefited personally from the gratification of a ‘right’ solution well achieved. Demon tweaks were engaged in, witchlike mods, to the receipt of the glue tried – and we had a deck laid 1904 style. I will give those clues to any genuine applicant free! The result is a joy and though there were one or two leaks they were easily spotted and the hard bits raked out and redone. It is watertight even in a heavy sea and even remained so after a long drought when the glue did its proper thing and contracted into the groove; in fact the level of the top of the glue is a very good hygrometer! Considering that deck is 75 years old and has been through a major fire says something for the technique alone. The Jonahs are confounded and the curve of the unbroken planks accentuates Strange’s beautiful lines every time I get on board.

The next major item, that largely went on concurrently with me raking the decks, was the interior — there was none. Like old houses the interiors of boats are a very personal thing and Sheila’s had changed over the years to suit the tastes of her major owner to whom her survival is entirely due. It bore little resemblance to whatever might have been there and Peter Mather had removed it to start again. I had carte blanche, a completely bare shell. The yard had seen my lunatic efforts on the deck but since I had done it myself, merely thought I was mad; when I asked them to remove every speck of paint from the inside of the hull, and meant it, they definitely thought I was certifiable since this was money I was spending! I insisted it was done right up into the eyes of the boat and round every frame. She looked superb, the timber sparkling as new without a fault in it, which fact helped me defend myself against the Jonahs who had called me a fool for buying her without a survey. Few people could understand that I was buying a piece of history, not a mere boat and that marline spikes and haggling were entirely inappropriate. It is no particular merit on my part that my judgement by eye was not faulty, the hull proved perfect; far more a tribute to Cain who built her and Jim Wilson who maintained and sailed her for so long. The bottom coat of paint was found to be cream, a wholly satisfactory colour, and cream she is inside. It is light and stylish, entirely lacking the anonymous glare of the pure white of most modern boats and largely contributes to her surprising feeling of homeliness; it also has the merit of being the original. As the photo shows the massive grown frames have been left varnished on their outer edge. I did this because these frames are placed at exactly the section points that Strange drew on the plans. I can only suppose that they are like this because Cain lacked any lofting facilities and the easiest method for him was to rebate these huge grown crook frames into the massive keel at the correct station points and plank up from that. She was built in a tiny one man shed on the beach and most of the normal boatyard facilities were not available. The varnished frames are a fine feature. As hinted above, her construction is a little unusual since these frames are rebated right into the enormous keel-and-hog-in-one which as it appears at the cabin sole is over 1 ft. across and nearly 18″ deep. Every rib is also rebated in which results in immense strength with a flat sole and no floors except one at the maximum turn of the bilge for yet further strength.

The bilge is a joy to heep clean as a dust pan can be got comfortably in !

Having achieved the sparkling interior the question was — what to put in ? There are no details on the plans but mercifully just before Groves sold her he drew a picture sitting in the cockpit of ‘Sheila snug at night’. All the essentials were there down to his sketching materials on the table and the instruments on the bulkhead. A strip of persian carpet is on the cabin sole, a tribute to the fact that he spent some three months of the year in her at a stretch, I wholly agree with his choice and my piece has nearly the same pattern, it is well worth the small extra effort it involves. The hunt for a matching pair of period instruments was to take over a year but was achieved in the end and with the original bronze portholes is exactly what Groves would have known. As far as could be seen, he had a Clyde cooker placed across the hull immediately behind the mast — as far as could be seen ! The drawing does not provide enough accuracy to measure from so I still had to produce some lead dimensions to build with. This proved extraorinaryly difficult until I found some guide ideas in Hiscock. I was mindfull all the time that she is so small inside that the heights and widths had to be exact or she was going to be impossible to live in. Sets of laths were nailed together and a start was made.

I decided at an early stage that originality and Clyde cookers were two different things. The drawing was so unclear here that I quieted my conscience and by a subtle rearrangement of conception the interior looks the same but the cooker, a Taylors Parafin lies next to the cockpit doors on the port side, with a wet locker opposite it. The exact height and width of the bunks allied to their fitting in with a full width chart table took quite a bit of juggling as her cabin roof is very low. Intense care and mich fiddling has produced an arrangement in which you can sit with your head erect, just, with a reasonably wide bunk and a wide cabin sole as shown originally. The seemingly low interior is well worth the sacrifice as it is possible to sit and steer fully protected yet see over the cabin top.

The arrangements to achieve a cabin table of complete stability, strength and size yet which would disappear completely when at sea and form a chart table for a full Admiralty chart caused much heartburn; her maximum beam is 6 ft. 9 ins. It was achieved and is much admired; involving divergent thought by me then a splendid effort by the shipwright. A certain amount of quite sophisticated machining in bronze got incorporated but I think that Albert would approve. The result will seat a party of four for dinner.

Groves spent three months at a stretch on board. Strange spent much time writing to the press about the exact arrangements of small boats, and I intended to do much living on board myself and with the minimum of temporariness and unplanned inconvenience, therefore continuous thought was always being given to storage, yet with the proviso that the interior should look as it did in 1905.

This meant not allowing any space to be wasted and also that every space should have a planned use and be designed for that use and that there should be an exact place for everything that one and the boat needs. This is my own personal feeling amply backed up by Strange. The bunks were constructed internally so that they had lifting lids and each presented a full flat suitcase for for the storage of personal clothes for quite some period, and not as normal in very small boats — all screwed up.

Groves spent a very leisurely time and his water supply was an oak barrel on deck, which I still have but I reckoned that since it is a particularly nice affair was likely to get pinched, so for water I indulged in a solution that fitted her modern style of use (weekends) and that I hoped Albert would have approved of if he had had them around. Underneath the suitcase bunk units are two plastic (oh dear) crewsaver all connected up out of sight which, with some subtle arrangements deliver twentytwo gallons of water to the tap, that came out of the original barrel, which I have placed by the stove. This is immensely successful and is quite undetectable and I still do not think that a solution of this type to this sort of problem detracts from the “Strangeness’ of the whole. Under the heads of the bunks are lifting lid lockers to take the sleeping bags by day so that they are not floating around while sailing.

A small detail that Groves did not have (and did not need in the Hebrides) but which the single man on the East Coast needs is an echo sounder – but how to hide the grey plastic, have it unseen while not in use yet immediately available on demand, without altering the cockpit or cabin, with the added problem that Sheila has a pair of full length cabin doors which fold fold back into the cockpit. More mental struggle produced a solution that even I am pleased with and fully fits the spec. The sounder vaas taken out of its case and modified to fit into a cabinet -made mahogany brass edged box which swings on a pivot inside the starboard side of the cabin. When not in use all that is seen is a magnificent brass inlaid box, ten seconds has it swung and locked in full view of the helmsman: the battery is remote mounted for easy changing. Albert, I hope, would have approved especially as the bo’sun’s locker contains a proper lead as well.

I had determined to use only paraffin lamps so this involved another major search for good period ones. The very real science of the paraffin lamp seems to have been lost in modern replicas, the exact proportions of all the component burning parts just does not seem to produce the splendid flame I get out of my Victorian ones. Lamps necessarily means a lamp store and the area just aft of the mast under the chart table (when at sea) contains a lamp store (with fur lined compartments for glasses) a shipwrights store and an engineers store so that I can do practically every job on board without recourse to outside help. There is a timber store as well. Tucked under the extreme forward ends of the bunks are lift out boxes with nav. instruments and a games compendium.

The essence of a Strange design is simple rig and few sail changes, if any, so it was reasonable to arrange the sail store forward of the mast which area would be a nuisance to get to for everyday living yet not difficult for the very rare times that I need to get a smaller jib or, when playing funny games, the mizzen staysail.

The cooking and crockery area I determined was to be perfect. How exasperating to have any form of crashings when sailing yet how boring to have to some complex ritual known only to the owner to to perform to prevent this happening. To start with I had commissioned a a complete set of stoneware for Sheilas 75th birthday designed upon lines I deemed suitable for boat use. As a frippery they have two gilded medallions on each item commemorating various people and dates and there are enough pieces for a three course meal for 4 without washing up (this means I can be lazy and wash up supper in the morning after breakfast and the dirty items lie soaking on the after deck at night when conditions seem to indicate a quiet night! ) Two medium pans with lids (the most expensive non-stick I could buy, a superb frying pan (the same), enough eating and cooking irons as above and, of course, the substantial stoneware coffee pot.

All had to be got into a space 18″ cube with full access and no rattles. This job was actually done in the middle of this Summer so was not seen at the A.G.M. I was so run out of ideas by this time that I dumped the whole horrible pile on the shipwright bench and said “fix it Colin”. Mercifully his faith had been restored in my sanity by seeing the ship sailing so he set to to solve this conundrum with a will. He did it and it is is wonderful and has the added advantage that you can make your sail with the lee pot of coffee and let it infuse in perfect safety under sail with the lee decks under. I spent a bit more on the Taylors Stove than in I need have done and got one with a reflected heat oven, very compact and a real boon. The sense of wellbeing engendered by being able to make supper and put it all in to keep hot, go and do the bit of anchor adjustment or whatever and come back to hot dinner and a carpet on the sole is out of proportion to the small extra effort it required to sort out all.

The original plans show a plank of wood across the hull at the one point of maximum beam labelled ‘fixed thwart’. This, on a Humber Yawl, would have been just that but on Sheila it is a boxed structural section and is the first bridge deck built into a yacht. Naturally its integrity had to be maintained. A smart panelled door is fitted to the side, facing the cabin and the whole boxed section becomes a perfect food store containing also the pump for the water. When the door is on nothing can be seen but when off the whole area is in cooking mode and is lit by one of those excellent half-sphere decklights let into the top. I was very lucky in being given an original ‘orange squeezer’ decklight and three round ones. I made them all decorative bronze mounts and used the ‘squeezer’ in the foredeck where it produces much light and a of class and gave the other two to worthy friends touch.

The whole of the interior is made in pre-war, Burma teak which contrasts well with the pine cabin roof and matches the teak cabin sides and cockpit. Here again known I was able to acquire all this simply because it was known where I was going and the bloke I got it from approved and sold it for a song; I was deeply grateful not only because I could not have afforded to buy it for real but because teak of this quality is simply not obtainable now. This lovely wood adds a sense of quality and permanence, the sense of assurance that good furniture has and which any boat built now, except the most expensive, lacks. It is a curious fact but it is noticed by everyone who comes below. They comment immediately how snug and permanent it all feels, all in a space hardly 10 ft. by 6 ft. Living in it quite a lot I agree and would vote the whole affair very definitely worth the effort.

Gaff boats have quantities of extra poles and yards and these always look untidy lashed in the rigging (the topsail and its yard and jackyard is 14 ft. long) and my passion for neatness would not permit this so they all disappear up under the sidedecks held in place by sprung lashings, quick and simple.

Concurrently with this the outside of the hull was attacked. She looked all of her 75 years in her old paint so the whole was scraped to the wood. It was a revelation and further confounded the Jonahs who gave up pontificating after this. Beautiful, shining pitch-pine looking as though it had been planked the year before. The only defect was a slight lack of fairness caused by the fire in 1942 and to rectify this some planing and filling went on. I caused much disbelief on the subject of waterlines at this point because I was aware of how Strange drew the waterlines on his drawings. His habit of drawing his waterlines as though they exactly followed the sheerline gives his plans distinction and a certain style. I thought that it would look splendid on the boat, so, after much coercion, it was done. The results can be seen and although she sat much more down at the bow when finished, so many people commented adversely that I was obliged to admit that the gap between theory and practice was, again, profound. It was then painted out. During the Summer finishing fortnight a lovely red boot topping was added which everybody thought would be very smart. In practice, it is a disaster too because she has such little freeboard that the main colour, white, is too split up by the topping. It is a fairly modern affectation anway, so next year she will be plain white to the water with the cove line, a proper cut in one, filled in gold.

It had been decided that to stop the deleterious effects of drying out too much she would go back into the water half-way through the restoration. Before doing so I had one more major area finished, the steamhead and its associated fittings with the bobstay fittings. It was a Strange feature of his Humber yawl designs that they were sloop rigged with a standing sprit (jib boom?) and no stemhead forestay, The Jonahs came to the fore again weighing in with ‘what happens when the sprit breaks ?’ They failed to recognise the glorious advantage of such a feature — no foredeck jib tangles. One should not forget that Strange sailed much alone and was well aware of the horrors of going onto the foredeck in emergencies, so Sheila carries no forestay to the hull and things have never broken in 75 years. It never ceases to surprise me things how simple facts of actual experience of this sort fail to convince Jonahs against all their own prejudice. For peace of mind, though I gave some engineering thought to this area, having spent some time as it were, on the lap of Claud Worth. Anyone restoring a period boat should do so. He indeed, have strong opinions but they were based on a then, unrivalled personal experience of cruising and boat restoration and he had a strong analytical and objective mind. For him, a problem was there to be solved, not merely steered round or put up with and many of his comments are exceedingly germaine to the handling and structure of boats. I listened to what he say to me, down the years, and incorporated many principles and some complete ideas. The main idea concerning the stemhead was the Claud Worth Chain Pawl, a simple device he cooked up (and made himself) in the eighties to ease single-handed anchor work. It does. I designed mine to work on 5/16 chain and plaited nylon rope. It was quite a caper since the pawl must be self jamming yet instantly free on ‘command’ on both the chain and the rope. It does and is a pleasure to use.

The actual solutions to the gammon iron and bowsprit deck fittings were arrived at solely by close and objective consideration of the actual forces involved when under stress. Due to my passion for ‘a little more of everything’ I wanted to lengthen the sprit (a mistake) and as the old one was getting worn a new one was made. Instead of being 3″ round the new came from 4″ square. It was made from a split baulk of Norway spruce glued end for end. Careful design and ‘visuals’ result in a spar very much stronger than the original and little larger, The garmon iron is a light but very stiff steel fabrication with a bronze roller on one side and the pawl on the other, made to fit the sprit exactly and to run down the sides of the stem to be through bolted. In order that it should take no sideways stress, Sheila being far too narrow to make sprit shrouds any use, the sprit itself takes this stress by being keyed into the stemhead with a 1″sq, dowel between sprit and stem. Failure to do this means working of the gammon iron fixing bolts and fretting at the iron. The stem piece itself was replaced in oak and a new stem-iron made and the whole assembly through bolted. The stem-apron proved to be nearly 9″ deep ! A new hardwood kingpost was made which sits tenoned into the apron under the foredeck. It fits exactly through the king plank and is retained in position by a large, tapered wedge morticed through its centre under the deck beams and the king plank. The tail of the sprit is morticed into its front face.

With the bobstay correctly tensioned the gammon iron performs no structural function in the rig and it will require the whole foredeck to tear out or the sprit to break before the rig collapses. The sprit is so shaped that the point of maximun bending is the point of maximum section. The next weak point is the bobstay fitting to the sprit and to the hull. A forged stainless bolt with welded eye was made from material which was driven through an entirely new hole, the old one being plugged. It was driven right through the stem and apron at an angle so arranged that under stress it was not in bending, only tension. On the inside of the apron was screwed a stainless plate with a ramp on it to accept the bronze nut on the end of the bolt, the whole is light but enormously strong. The same caveats apply regarding the use of stainless steel here as earlier, except that in this case since the assembly is inevitably in contact with galvanised chain I shall replace it all this year with galvanised steel to match the gammon and cranse irons and their attendant stay chain. The same degree of trouble was taken with the cranse iron to complete the assembly to one standard. Also here Worth has some strong views concerning the placing of outhaul sheaves in sprits as he recorded many breakages of bowsprits immediately behind the cranse iron simply because this was the fashionable place to put the outhaul sheave — this severely weakens the spar. Many cranse iron designs seriously weaken the spar as well and are not above splitting the end grain. Sheila’s one is turned out of a solid billet of 3 1/2” diameter mild steel so as to slip exactly over the end of the spar and come to a dead stop and also to have the outhaul sheave placed in the unit itself beyond the point of attachment of the forestay, in an area of no stress.

Substantial steel rings are welded on for all attachment points. Due to care in design it is only thick where it needs to be so so it is very much lighter than it looks. It is of immense strength. Initially solid chain with a special tensioner was used for the bobstay and although this all sounds massive, the proportions do, in fact, look very neat and the many eagle-eyed critics have not adversely commented. I soon found that for river use it was necessary to have a reefing stay to reduce mooring rope chafe and the fearsome chain to chain rumbles in the night so I fitted a three part purchase at the top end of the chain which comes back to a cleat under the sprit. It works well but the rope purchase is far too stretchy to be of any value as a stay and will have to be made in wire for effective use at sea. There is one caveat concerning reefing bobstays. One must not forget to set them again before going sailing! I spent a whole morning in considerably brisk conditions with no stay at all having forgotten to reset it after getting the anchor, with the strength of everything, probably no danger in the river but tricky at sea!

By this time Sheila had been out of the water for nearly three years and it was becoming painfully obvious despite her massive construction. Much stopping and a little light caulking went on, the caulking being done very lightly to ensure that no uneven stresses were set up when the wood began to swell again. This point is important and many good boats have been spoilt at this stage, especially if lightly built.

The caulking should be left alone as it will largely rest in the place that it will adopt when the timber is stable again; attempts to make the hull tight in one go by tight caulking when bone dry will only distort it under the great stresses of the re-expanding wood. Patience is required. When she was put in, she did look a little forlorn; no spars, rudder or fittings and sticky tape on the decks.

She sank with some speed and Deben rose over the new bunkwork and looked as though it would stain it for life. Spirits sank as well as I was broke. She was put in a mud berth for three weeks last June and work stopped. Although I continued making fittings and planning I was, naturally, paying for the shipwrights work.

During the three weeks she did indeed take up quite a bit with putty squeezing out all over, though it was soon apparent that there were one or two main leaks that we could not isolate. We had stopped her drying out completely which I feel was a distinct advantage. I cannot help feeling that subjecting a structure such as a wooden boat to the considerable stresses each year caused by alternate wet and dry cycles is not good for the integrity of the structure and that allowing the water content (and thus the dimensions of the wood to stabilise is far fairer to the wood and fittings, especially old ones. I have proved this satisfactorily with a frail old clinker dayboat I restored. There is a very real difference between taking a boat out to stop it getting waterlogged and the fashionable six months out six months in cycle. Sheila has taken nine months to dry out and I suspect that there is more to go before she is as dry as her construction and reputation indicate she should be. A very real example of the effects of drying out were to occur later when we got tangled with the rudder trunking. Parallel to all this activity I worked at fittings. I added Harrison-Butler to my reading and went into as detailed a study of Sheilas rig as I could from contemporary writings and pictures, since no plan exists. Mercifully Grove’s pictures go into excellent detail, certainly enough to show the difference between what he knew in 1905 and what, I suspect, Pat Walsh substituted in the 1914 rebuild. With many differing plans in my head from all this theory I resolved to go back exactly to what was there in 1905 unless I could decide on a very good reason, unlikely to alter the performance of the boat in any way, for adopting any mods done in 1914. The only feature to fall into this category was the extension of the main shrouds to the cap, with a set of high set spreaders. I think she looks less ‘frail’ like this and since I wanted to set a jackyard topsail (as Strange designed for Mist) I thought it a good idea. The remaining functions of the rig, in detail, are exactly as Groves knew them The detail toings and froings engaged during this phase are too boring to bother with but the principle was to throw everything away (nothing was original), consider exactly where everything was going to be and analyse its exact function at that point, then design and make to suit.

The philosophy behind the results was the opposite of that adopted today. I wished to make everything as simple as possible with no fittings, or solutions to problems, that were ‘trendy’. I did my best to subjugate my instincts as an engineer, to be clever, because I wanted to go back to the solution of sailing problems with bits of rope and proper knots and dispense with the modern cunningly contrived hardware. Where I have used engineering I have tried to use it only for accurate assessments of stresses and their correct solution. I wanted to use, therefore, no proprietory fittings whatever; many fail to satisfy Worth’s standards.

The first item discussed was the main boom gooseneck-mast band assembly as Worth has very decided views on this, with which I agree, so decided to follow in principle, though, having a modern engineering works, I indulged myself somewhat in the actual execution. When I bought Sheila she had roller reefing and a laced sail to both boom and mast. Groves pictures clearly show luff and clewline with a loose footed sail and mast hoops. I suspected that this was likely to be very much more handy for a singlehander (Strange again) and so it has proved. It is certainly original. I spent some time simplifying the method of the reefing which is an improvement on even the traditional in simplicity and function. This meant that the gooseneck only had to provide a universal joint fixing of the boom to the mast and it was to incorporate the spider band as well. It was clear that Groves had all the halyards lead aft over the cabin top but either he was of enormous strength or I am excessively feeble since I could not even do this with the topping lift. Everything goes to the mast band. The actual design of the unit was governed by the following spec. The fitting was to include belaying pins for all the ropes on the mast; it was to have completely universal movement for the boom including rotation to allow for the set of the sail; it was to be made of uncorrodible material in its own right and was not in any way to be ‘fixed’ to the mast nor to impose any point stresses on it. I had the good fortune to have the original mast in unbelievably perfect condition and it was worth preserving its integrity which meant that the fitting had to be held by friction to avoid the tearing loads imposed by bolts or screws and the whole had to be moveable since I had no method of knowing exactly where the final resting place of the boom would be. The result performs all these functions excellently but is in no way a budget item. Mercifully I did it early on, I do not think that I would have had the courage to go so far or so expensively later on. It is made of solid aluminium bronze, being a huge but thin, octagonal clamp turned to be an exact fit on the mast, some 6″ deep. On it are welded copy-turned aluminium bronze standoff bosses to take four bronze belaying pins. It slips up the mast and is clamped, with bolts designed into it, round a heavy rubber gasket. It is moveable and spreads the boom loads so well that the varnish is undamaged. It has a matching spider band lower down the mast with 4 more pins. On the rear side is fitted the universal joint assembly made to similar standards with all the moving parts insulated from each other with ‘acetal’ washers and bushes. Although this all sounds as though it does not fit the simplicity idea it only performs two functions but it does them properly and will do them for ever with no further attention. It only required one mod, in practice since I had underestimated the clamping loads required and early on in its use, when putting an extra effort into the jib luff, it came off its gasket and whole affair shot up the mast completely demolishing the rig, much to the enjoyment of the Clays. Bigger clamping screws and rubber instead of the original leather have proved a complete solution. The boom is fitted into a solid turned sleeved end which is part of the joint. It has welded onto it the rings for the main tack and for the reefing hook.

For anyone who would like to think of using it I will describe the reefing arrangement. The luff of the sail has two large brass cringles as has the leech, one cringle for each of the two reefs. Between them stretch two rows of little eyelets, one row for each reef. There is on the boom at the tack a large single hook laced to one of the welded rings and this hook drops through either of the luff cringles. Spliced directly into each leech cringle is the end of a single leechline. Each line runs down the sail (one each side simply not to put a set in the leech due to two lines on one side) directly to the boom where it enters the boom through a hole cut in the top surface, one hole for each reef position. The holes are cut only just larger than the line and are cut at the angle that the line adopts when it is taut with the reef in place, which is in practice at about 45° through the spar in a fore and aft direction.

Each one comes out at the bottom of the boom and runs over a polished pin (to stop the line chafing the timber) and runs forward up the boom in a channel cut under the boom to accept not only the two reefing lines but the main clew line as well. They all go to the forward end of the boom on cleats as normal. Because the main clew line is always in a state of slight motion when the boat is sailing it is supplied with a large thin sheave cut right at the end of the boom incorporated into the mainsheet fitting. The whole thing is merely a simplification of a full traditional ‘lines’ system but has a number of advantages. The first is obviously far less rope. The luff hook is far quicker to use than a line. For a sail this size (and probably up to about 350 sq.ft.) a single purchase for the clewlines is plenty and presents one with half as much rope fall to lose and is quicker to pull. Since there are half the number of lines on the sail there is half as much chafe. The whole thing being tucked away as it is there is less rope to get tangled and the whole is much neater than the standard ‘B’ block arrangement. Reefing perfection is achieved when the geometry of the peak hoist and the gaff strop are so arranged that the strop traveller moves up the strop, when the luff is hauled, so as to leave the set of the sail exactly as before without recourse to the peak halyard. After some mild experiment this has now been achieved. The result is pure magic. Since Sheila will sail herself even with the wind well on the beam for the time required, reefing is merely a matter of letting the mainsheet out just enough to take the main drive out of it and pegging the tiller. Although this sounds like an ‘I told you so’ it is far from it — much a tribute to Strange and simplicity. One then steps forward, releases the luff balyard and drops it enough to engage the hook immediately pulling it tight and cleating it. Taking the relevant clewline under the boom, give a smart heave until the clew is home and cleat. The reef is now in with an extra thirty seconds required to pull the slack out of the unused (second) clewline and cleat that also. The sail is driving, no sea-room has been lost and all is done by one in about a minute and a half. When the sail is fully home again and working hard the bunt of the sail is captured by passing little specially made toggles (just a flag toggle on the end of an eye splice) through the buntline cringles, one for each hole. The system works so well that in a tight spot with two of us I was able to rush forward and have a reef in in about fortyfive seconds while the crew shot us through a particularly tricky anchorage with full drive in the sail at all times. The tidying up was done very much later after the fun subsided. I have gone into this in some detail because I believe, like Strange, that this sort of thing is at the very heart of a good cruising boat and is the very essence of the method. My contribution to the thing is marginal, the kernel of success has been a determination to examine and use the traditional methods without fear or favour and see what they had to offer. The small improvement I contributed is as nothing to the simplicity of the original conception from which it stems and which had been in use for generations before Strange. He knew these advantages of the loose footed sail and he may well have known the now well proven fact (wind tunnels!) that a sail allowed to set well clear of a round mast on hoops is far more efficient than one laced to it. You have to go right to the extremes of laminar flow section masts and luff grooves to achieve as good a performance as a well set masthoop! I am satisfied completely with this return to the original, it has proved, in this area annway, all I set out to achieve.

Proceeding up the mast to the other functions the Worth principle of not screwing things to the mast, especially things that take stays has been maintained. A quick analysis of the forces involved shows why. A complete set of new mast bands to take all the shroud and balyard points were designed on the following idea. A thin steel ring, some 2″ deep, was made with its inside diameter tapered to a slightly greater exter than the mast at the point at which it would sit. An aluminium bronze ring was made, slightly deeper, the external surface of which exactly matched the inside of the ring and its internal surface exactly matched the diameter and taper of the mast at the same point. This bronze ring was then split and gapped and let rest on the mast at the chosen point and the ring driven over the top to form a self-locking pair. Heavy rings were welded to the steel rings at the appropriate positions for the job in hand and the resulting bands galvanised. Initially they required a little encouragement to lock but now they are in place they are completely solid yet come free at the tap of a hammer and show no marks at all. The rigging can be spliced directly to them, enhancing neatness and reducing weight and chafe. The rigging can be removed simply, in units and cannot get mixed up in store. One way and another a somewhat elysian situation.

Since I was planning to add a topsail I took the chance to add a pair of occasional backstays to the rigging purely fon the situation Her original well off the wind when the main is not acting as a backstay. rig never used backstays since the after stays come surprisingly far aft and she has survived far worse conditions than I shall ever see without them. For river use not having them is a joy and the rig shows no inclination to fall down, though it is fair to say that it is not possible to keep the jib lush as tight as a modern one. I have set these stays up on a little four-part purchase and cleat system which is more than adequate since they only come to the midpoint of the hull where, I am told, a set of legs were mounted. So far in their very occasional use all I have noticed is a slightly increased feeling of security off the wind; I have had her on a dead run with too much sail up without them and she is still in one piece so I suspect Strange knew exactly what he was at.

The mast was finished off with new cheeks and sheaves for the topping list. with roller reefing the topping lifts have to go to the end of the boom, thus allowing the gaff to ‘escape over the side’ when taking the main down; or the complications of lazy jacks indulged in — doubtful things at the best. Without the need for rotation of the boom the topping lifts can go to the point on the boom at which the gaff can never escape The original them and the sail always comes down tidily as a result. oak ball was replaced on the truck with a large bronze spike as a seagull deterrent. Immediately below this but above the cap shroud band are cut the sheaves for the new topsail hoist and below these the chocks to take it.

The mast was finished. The mizzen was treated in like but lesser manner except that provision had to be made for the topping lift to perform a brailing function on the boom. The original method used for furling the sail is just to let the sheet fly and pull the topping lift, which passes round both sides of the sail and boom, brailing the boom and sail up to the mast in one. The gooseneck fitting had to perform this function with the sail at any angle. After a couple of simple solutions had broken (mainly unbrailing the sail off the wind) I set it up with a rope strop well seized. It has the merit of complete flexibility and simplicity and apart from being able to see when it might give up it is easily replaced with more string.

The original rig had gaff jaws for both main and mizzen so the saddles were put in store and new laminated jaws, with tongues, made. The Jonah’s winged again but this time I fear they may be night. I know that Groves broke a jaw early on and a crack has developed in mine despite a level of design and execution of the highest. I shall try widening them this winter to reduce the twisting loads imposed off the wind but I fear that even then they may hail. A pity, since they are exceedingly smart

The originality of the rig was completed by spliced galvanised lines running to Lignun Vitae deadeyes. The deadeyes are a slight sophistication for a boat this size since mere lashings could have been used. Tom Holditch made them for me and they look splendid and are a joy to use. Rigging screws often result in overtightening of gaff rigging and you cannot see when they are going to break ; deadeyes and rope solve these troubles. The deadeyes were another delightful exercise in themselves. Lignum had to be found first, not by any means readily available at your local D.I.Y. Then Tony made them. Have you ever looked closely at a deadeye in real life? With the best will in the world we made them wrong although you cannot see this. I learnt exactly how they should be made and have now found out why and one of the old local bargees told me exactly how to reeve them and why; it was all fascinating and one of the essential facets and pleasures of restoration.

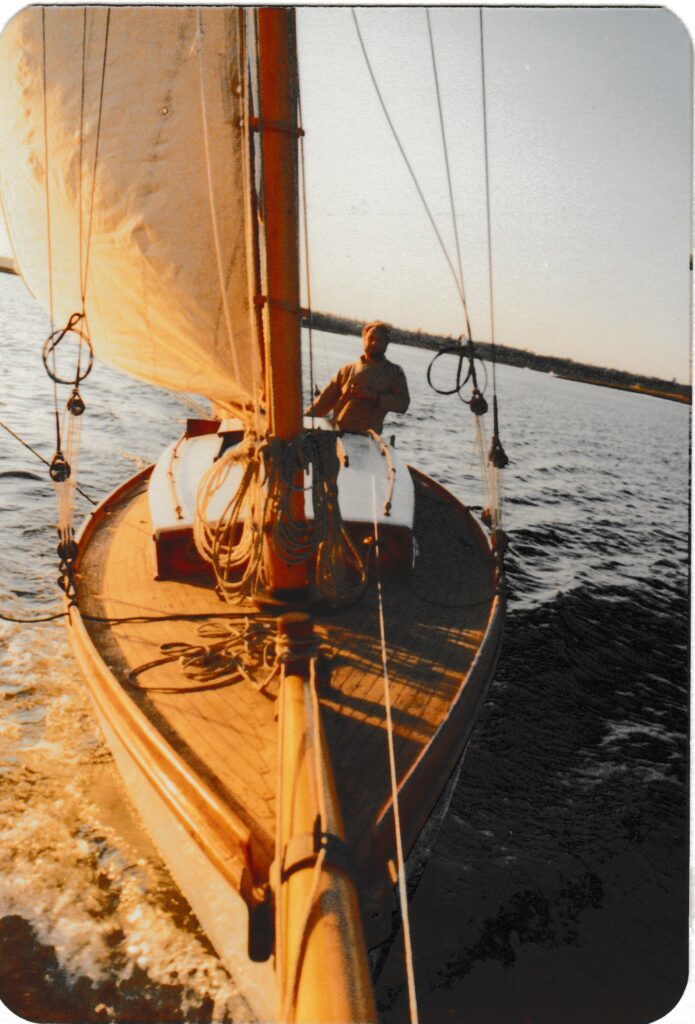

Hiding in the loft by this time was the new suit of sails. Again I had determined to be original and had the wherewithal to be so. We are lucky in having a local sailmaker who regularly cuts cotton and from whom I had a cotton suit for a dayboat in the past. A suit cut exactly as original was ordered, vertically cut, loose footed and with the reefing arrangements described. When I bought her she had a virtually new suit of terylene sails fitted by Jim Wilson shortly before he sold her. He is a tall man and naturally less active in his later years. Sheila’s boom was, and is again, low. So when he had the new suit he had the main cut as with a reef in and raised the boom and had a smaller jib and mizzen. She is such a surprising performer that I do not doubt his contention that in most winds her performance was largely unaltered and he would not have needed to reef till nearly a gale. It did nothing for her looks as a photograph he showed me indicated. I had fallen in love with a dream as drawn by Groves and, therefore, this is how she had to be. The cotton ones had to be measured out from guesses and ideas most of which could be done relatively easily, except for the exact peak of the gaff a particularly Strange feature. I copied this from Mist’s sail plan. The only mistake has been the jib. It got it cut mitred by misunderstanding and my enthusiasm got the foot and leech too long. It does not look period and the foot picks up the sea and although a real driver it is slightly too large. It gets recut this Winter. Mitre cutting did not become common till slightly later and it would match the main better that way. The main is a huge success and sets really beautifully as does the mizzen, which I had cut later in the season after finding that the the terylene one really was too small. The considerable size of the mizzen and the mast’s adequate staying means it really is a very effective sail and gives her sailing character and manoeuvrability something out of the ordinary and entirely due to Strange who knew from his Humber Yawl background what a mizzen is really about. A real yawl is about being able to go to windward with just the jib and mizzen; Sheila will fine reach like this and this is, without a doubt, what strange knew about, wrote about and achieved. The yawl has been despised since his day because they have acquired silly little mizzens which you cannot sail with as a main sail. Most yawl mizzens come down when the first wind blows. Sheila’s stays up unreefed till force 6 and the main has come down completely unless there is pressing need for close windward work or great speed. She will sail to nearly hull speed in a force 6 with the standard jib and the mizzen unreefed as long as the wind is slightly free; the feeling o control and comfort thereby engendered is exactly what Strange preached that cruising should be about, it is.

Having essentially finished the fittings and details, though taken as a heap of bits they seemed to be never ending and were made over a long time, we started back on the hull

We had come to the engine, rudder area. When I bought her she had a long-shaft Seagull, side mounted, which I gather was only used for going through the Crinan Canal and harbour manoeuvres, for which , no doubt, it was excellent. For dodging the shipping in Harwich harbour or nipping across separation lines at the required Board of Trade angles it was a non starter. I had quite a bit oh mental agony over the engine. If I was to keep my trust and not spoil her appearance or her salling qualities ( reputed) I had a difficult task as she was definitely not designed to have an engine. The solution had to go under the cockpit floor without raising and should not at the same time obtrude into or cut the bridge deck, The propeller I decided must be central and there was only a small latitude on its position due to the angle of the sternpost. The engine should not be heavy enough to noticeably effect the trim. This ruled out any modern marine engine and many period ones as well. The hunt ended when I found the ideal plot, except that it was not a marine engine. It was a little flat twin air-cooled four stroke of some 300 cc. giving 6.5 h.p. It has a large aluminium flywheel fan and was buillt to G.P.0. requirements for generator use. It is aluminium and can be lifted easily with one hand.

In order to get it really low I made it a steel flywheel of smaller diameter but having the same moment of inertia. Due to the relative positions of everything there was no chance that the engine would drive the prop direct so a simple vee belt couples the engine and the tailshaft giving the opportunity to choose a suitable reduction to suit the performance of’the engine. All is not done since the propeller must be arranged to drive the boat and the top end of the tailshaft assembly must have provision also to withstand the load of the vee belt drive, for which normal tailshaft glands are not designed. A cunning arrangement was designed to hold a taper-roller bearing on the end of the propshaft supported in a housing in the hull , thus driving the hull and supporting the shaft. I have not managed to get the unit coupled up yet and since Sheila goes so well have not felt the need of it : it will all get finished this Winter.

The oniginal rudder was formed in a solid 2″ post and was tapered off to the after end. Since it was faired into the deadwood too it was a very nice affair. It all had to go due to the propeller cut-out. This meant the construction of a steel post in two halves with curved joining pieces all welded together.

Thank goodness for an engineering works. I was able to muke a very superior job with the minimum of effort, machined to take the original bronze rudder head. It was galvanised complete. The rudder head itself caused many hours of loving labour. Here begineth lecture so skip next piece unless interested in hand file work.

It is one of those magnificent Victorian things, angled so that the top is horizontal, upon which, in this case, her name and date are engraved with squirly lines round.

The whole thing with its surround plate, which gives her builder’s name and port of building, was in a fairly battered state. answer to these problems is hard work with files. Any attempt to do a heavy job with a polisher will only ruin the shape and polish away the sides of the letters. The method is this, which is true for any restoration of this sort. First regenerate the original form of the piece without any of the dents using a sharp second cut file, flat, Take care to go very gently and always keep the original shape as you go. When all the dents are out and your file marks are perfectly even then proceed with the swiss needle files to remove all the file marks created so far, making sure as before to keep the shape. Before getting anywhere near polishing it is important to get all the marks of the first work completely removed. with a sheet of 600 grade wet-and-dry paper and polish out all the marks of the Swiss file work using plenty of water to keep the paper cutting. When you have achieved a perfect silk finish then grab the brasso and a hand cloth. The result is well worth the effort. The piece will look virtually as new and will not have the amateur appearance so often seen when all that has been done is to cram a buff on the job and polish all the dents in and blur all the edges. The result sat on my desk until the rudder was fitted. A magnificent new oak tiller made by a cabinet maker friend which was fitted to the stock, as originally with a tapered iron spike which sits in the rudder head and is bolted into the tiller, finished off on the outside with fancy brass dome nuts and all varnished. It is all pretty splendid and since it is the thing with which you communicate to your boat, so it should be. It has to be admitted that the tiller came almost last and tatty bits of wood were in use for some time.

In order to raise morale at this point some flash was embarked upon. There was no toerail. A new one was needed and I had no intention of spoiling the boat with guard rails and such. This meant that the toerail had to be a serious affair. I was much prompted to this by the incredible feeling of insecurity when walking along the deck in the mud berth with no toerail at all. I did some drawing and then went to buy 100 ft. of 4×3″ teak. When I showed the draning to the shipwright he had one of his bad turns and it was only that, by now, they had come to trust what I said that we got it done. It is 31/2” high and is straight on the outside to fit the line of the hull. It rolls over at the top with a large radius to form, in section, a canted over ball form, and curves outward again, down and inwards to form a large internal convex radius which ends on deck with the foot of the rail some 2 1/2” wide. The large internal radius acts as a trap for feet even when the decks are underwater (quite unlike the normal bevelled toe rail) and the large foot area makes for very secure bedding. The whole section (25 ft. long of course) had to be hand planed and scarfed. It then had to be sculpted round the chain plates and scuppers and fairleads cut into it. It is a work of art and nearly caused a fight as I got the section slightly too substantial first time and it would not bend round the hull and had to be re-planed. When it was in place on the bare hull (having had nothing there at all before) it looked too large and my heart sank. As more things got added on it looked better and better and non the is sailing it looks and works superbly and has been the subject of much comment. It was a near miss as it was very expensive.

Having had a bad fright here we embarked upon simpler things inside. As confidence grew again we did the cockpit sole Isolid teak) and the cockpit was recreated. Again I determined to be as exact as possible. It is essentially simple with an after thwart across the end for the helmsman which is also a box for storage. The sides are lockers to which we made folding down doors on hinges to match the one original door on the counter locker. Two more tiny ones were made for two little lockers right at the front of the cockpit. Everything matches and is in teak as was the original though it was only afterwards that I discovered that the style of panelling was different on the small ones. Personally I hate locker doors that come off in your hand and have to be put down somewhere before action starts, so mine were all made with hinges and cabinet makers pulls into which we engineered cabinet makers locks so that the cockpit can be left locked. It all looks very smart and works very well in practice. The height of the cockpit floor was adhered to except that to clear the magneto on the engine there is a sloped piece in the centre. This proves, by good fortune, to be a good thing as it forms a foot stop when sailing or leaning over the side to rinse dishes. I am glad that I did leave the general dimensions alone they prove to be perfect for the job in hand.

Although many of the things that 1 have recounted were now done by no means were they all in place and we were well into February with Albert’s A.G.M. looming in April. Desperation began to reign at exactly the time that I began to go broke again. It was essential that the job was finished as there would be nothing to show if it was not; so I pressed on well knowing that the Fleet prison was not far away. The topsides were given their finish coats and the Kobe green put on and she was put into the water and sent round to her mud berth. I had a fortnights holiday to try to get some of the millions of tiny details tied up.

This all happened at the time that we were moving my business into its new purpose built works (actually moved in in December) and the final holiday was taken first after we had had the works opened by the Minister of State. With one 10 year dream partially concluded in so splendid a way I was racing against time to conclude another 2 year one within a month. I was in a highly frenetic state. Doom set in as a persistent leak could not be cured and it was far too real to ignore. We thrashed round with caulking and stopping to no avail, finally deciding that the rudder trunking was the culprit. Very elegant things rudder trunkimg are until they go wrong and this one was very wrong. The trunking is built up like a barrel of vertical strips which are then encased in a substantial structural frame, joining the deck to the hull. During the drying out the sections of the bannel had dried and curled up leaving huge gaps. The trunking is 3 1/2” diameter and 2 1/2 ft. long so there was no chance of rectifying this except by dismantling the whole of the counter of the boat. Desperate measures were called for and I took charge here myself. We bought 3 ft. of 3 1/2 0.D. hard drawn copper tube 14 S.W.G. and some soft 12 S.W.G. copper sheet. The tube was cut to be a good fit with the bottom profile of the hull at the rudder and the copper sheet nickel-bronze welded to it to form a skirt. After this the skirt was completely softened. Then with a jack between it and the keel the tube was pushed up into the trunkink, being an exact fit, right up to the top and untill the skirt was flush with the hull. I then spent a happy three hours with a lange planishing hammer forming the shirt round the hull to be an exact fit and flush. It was nailed in place with many gripfast bronze nails being bedded down on lots of goo. This solution is final and proves to be so. It was expensive and by no means simple to achieve but the whole was done in a monning. The leak stopped.

With a huge sigh she was lald along the side of the boatyard wall ready to step the mast. This was to be the ultimate point to see if all my stuff worked so I asked two very good gaff friends, who also work at a well known boatyard, to give me a Saturday of their time. By now as the dream was coming true before my eyes I was getting less practical and more frenetic especially as I had had a diet of “getting things together” We spent a delightful day dressing the mast during which I learnt a lot and on the afternoon tide towed her down to Whisstocks marina, still without a mizzen. Next day one of them very kindly gave me another day of his time and in a lunatic burst of effort (remember that everything that was being done was ab initio and neither of us had seen it before together). We threw the mizzen in and tied the whole affair together with bowlines galore. I had had a completely new set of ash blocks made for all the running rigging and we were furiously stropping these up to suit each position as we came to it. Naturally we found that one vital size was in short supply and I still have one plastic block. It was a glorious Saturday afternoon and our furious activity was watched by quite a few souls as high tide approached. It was at this time that we found that the big new jib was too long in the luff, which sent morale to a low but having made up our minds that we were going to sail on the top of the tide we just hung on the one that I had bought her with. We got the feeling that this would balance the small mizzen that I had decided not to replace until I had seen how it performed. Ther were many well wishers on the bank of the marina as we towed out, hoisting sail as we did so. We went out without having tried anything at all and with no sort of reefing and there were a number of things that I had bodged at the last minute but by that time it did not matter. I strongly believe that in any activity one should set the highest standards and constantly strive towards them not letting them slip on compromising them in any way but know exactly when to freeze the ‘design’, get out a huge hammer, and hit it, and go. There is a nice point when one won’t achieve the overall without a spot of compromise at the last.

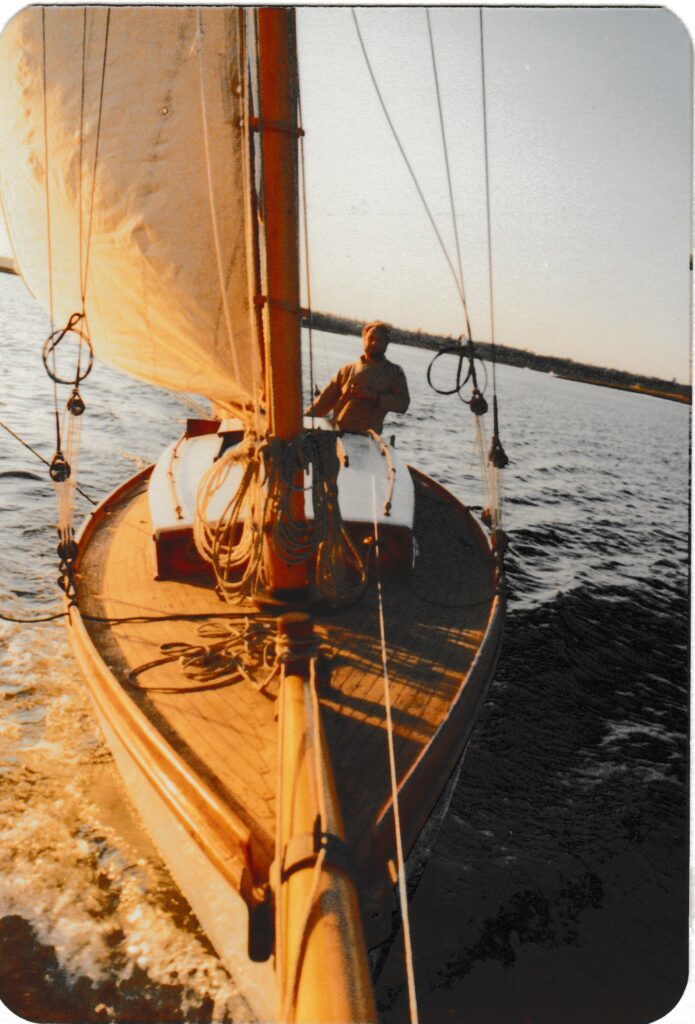

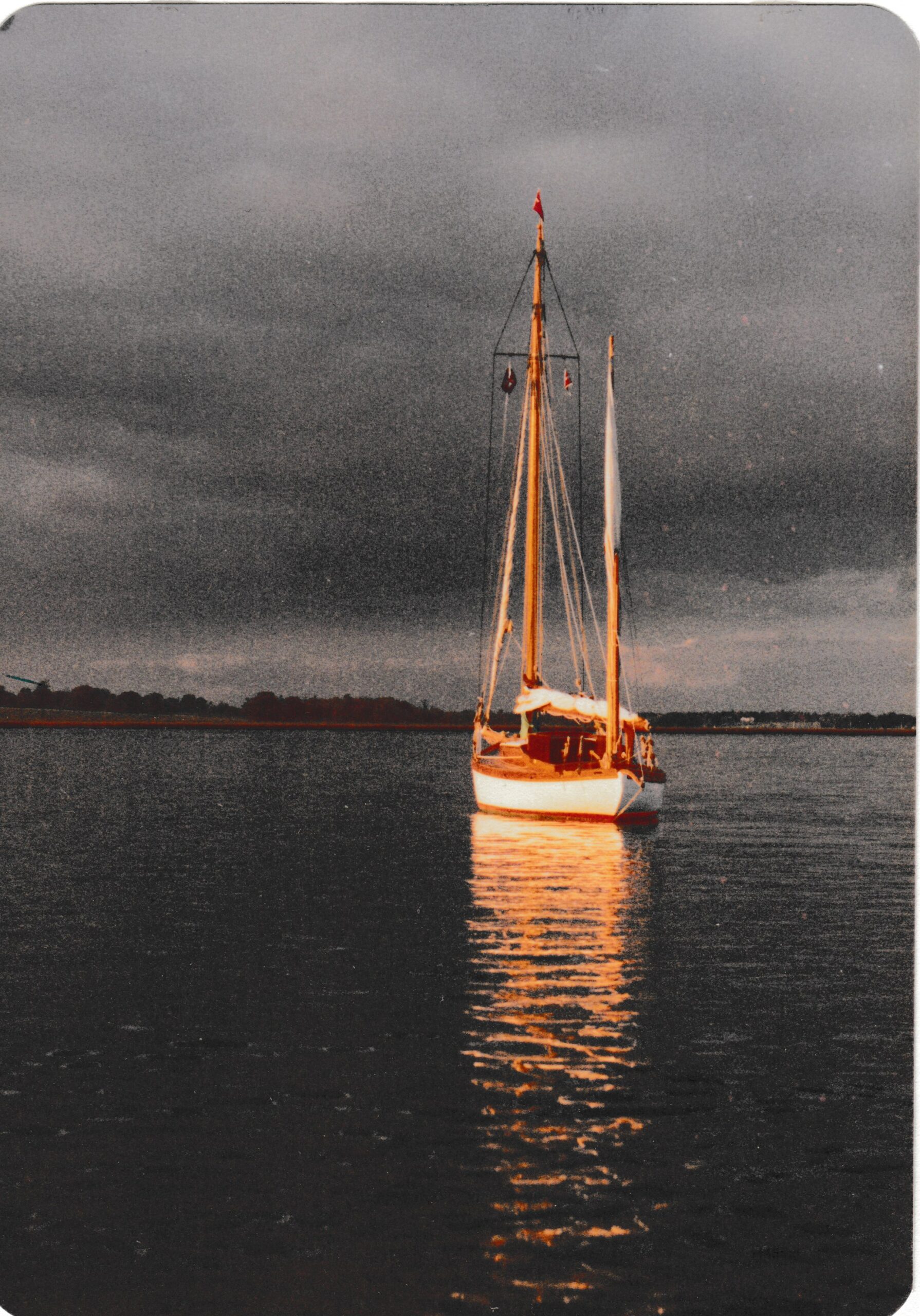

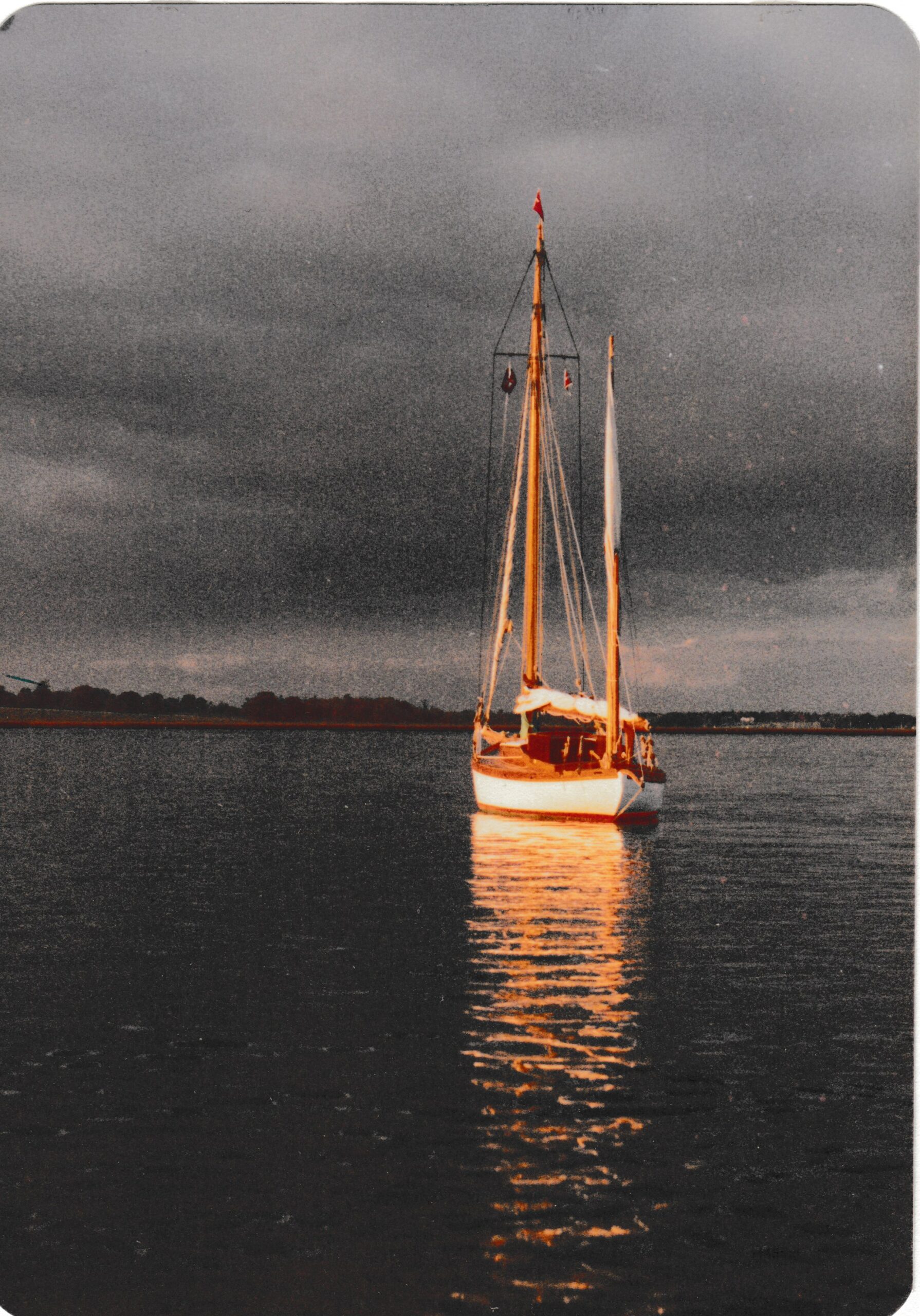

We had arranged to sail down to Waldringfield (a very great voyage of perhaps 3 miles) to dine with the parents of the helper concerned and I had put on board two bottles of excellent Moselle to take with dinner. On a broad reach and with the sails far from perfectly set we shot past the marina and vanished out of sight. This was the first intimation of what has now become to be recognised as truly sparkling performance and much feedback from watchers was gratefully received during the ensuing weeks.

We soon found that she really did go well. We had a very good yardstick as my helper has a gaff cutter built as a racing flush decked yacht some 10 years older than Sheila but quite surprisingly fast. It was soon realised that Sheila was closer winded (and now things are sorted even more so) and considerably faster. Even in the shambolic state she was in she showed every sign of balancing well and she was undeniably beautiful to look (and now that we have the right sails even more so). As the reader will surmise I simply popped. We opened the first bottle shortly after starting and set to. I climbed the mast and looked out over the Deben and revelled in it. We finished the second bottle shortly before picking up a mooring, which function I completely forgot, as the dinner afterwards. This was the beginning of a new learning and a much deeper appreciation of what Strange had done.

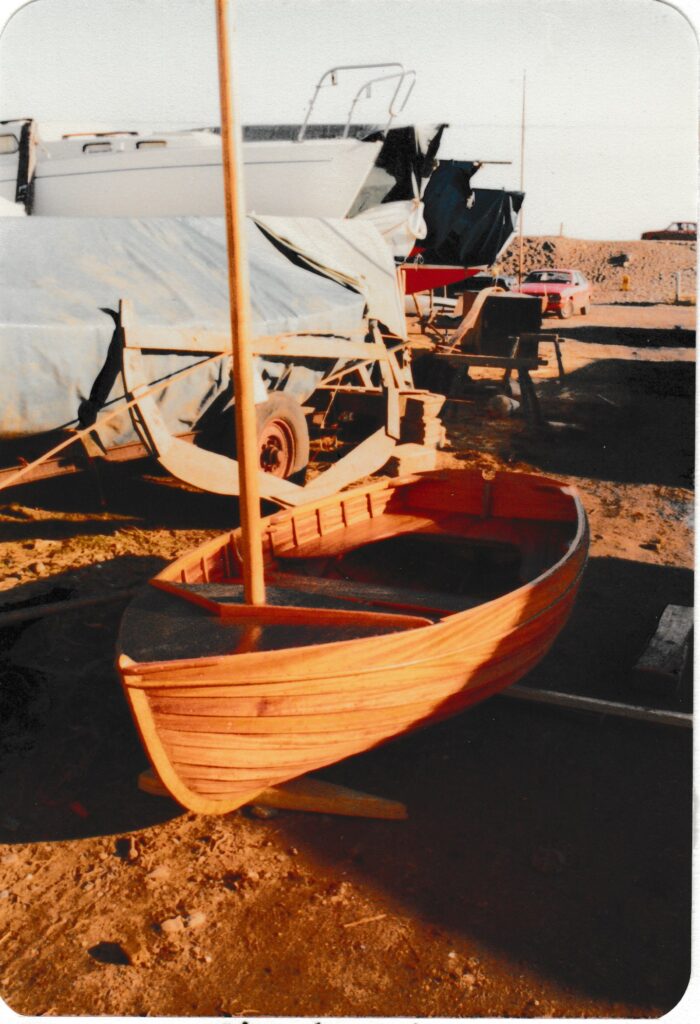

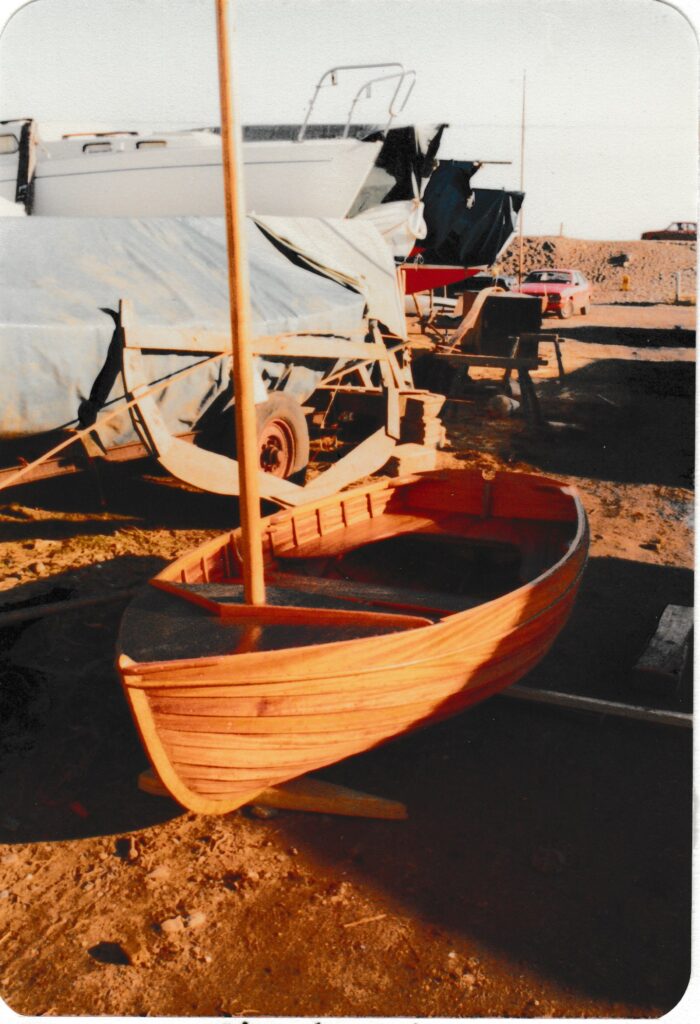

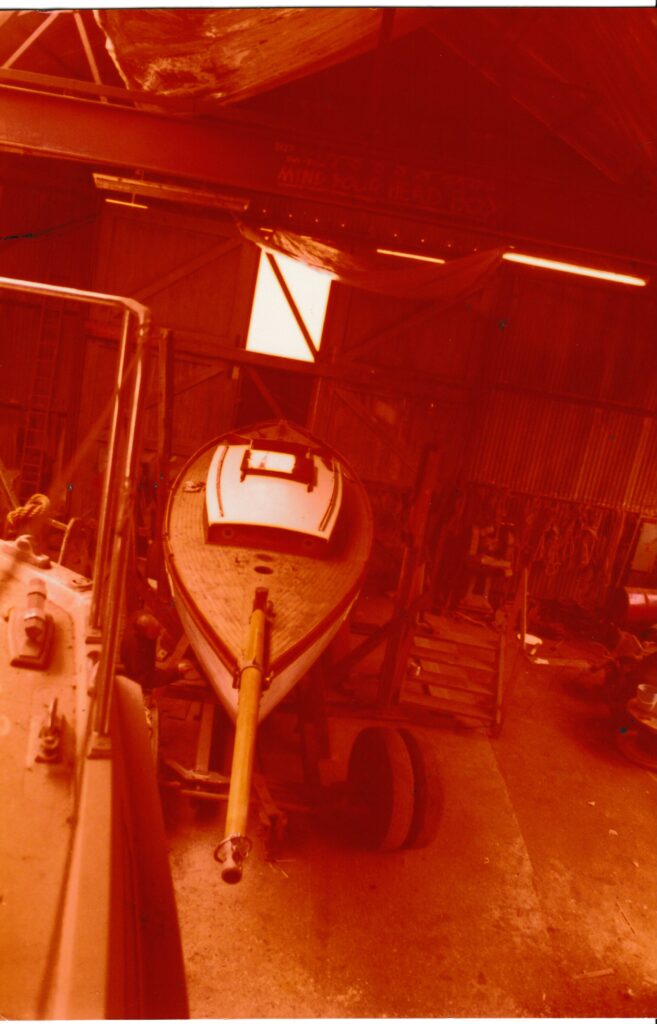

In order to celebrate her 75th birthday with something for Sheila herself I had determined to have built a proper dinghy as close to that one she is shown towing in the early Groves pictures as possible. Even on the East Coast this proved surprisingly difficult to get done. I found a builder whose son was apprenticed to him who decided that he would do it. I got some ideas from early H.Y.C. yearbooks and he added a number of his own (based on some local dinghys whose fame for speed was considerable). We added in some beam and more freeboard and a natty raked stem to satisfy the requirement that she should sail and away we went. She was built by the son as his apprentice masterpiece and she is all of that.

Mahogany on oak with a little foredeck she is 8 ft. long with a beam of 4 ft. 2 ins, and is a beautiful thing to behold. In order to ensure that such an expensive affair should not be stolen I had the transom heavily carved with her name S.P. (Sheila Parva) and Sheila’s name, and gold signwriting records her builder and town and the fact that she was built for Sheila’s 75th birthday; it is a pretty posh transom. She does row fast and is steady enough in a heavy sea to lay out anchors with and she tows well too. Towing her has one disadvantage in the river which one might not expect. Sheila with her lovely canoe counter makes no noise at all passing through the water, S.P. being clinker does. She is such a super thing to row that I can afford to anchor a long way from civilisation in peace and now to wherever the action is knowing that no effort is required. More often than not I sail as she sails surprisingly well – with a simple dagger board anchor oar ‘Roman Style’ as a rudder. This ‘rudder’ has many advantages such as being an oar, a pole for pushing or turning her round like a wind mill when stationary — bother rudders. S.P. like her parent is universally admired and they make a happy couple.

She has been sailing very considerably since. As I write she is virtually finished and I live on board every weekend — the magic has been fully realised. She looks beautiful and everybody keeps saying so. She performs uncannily, making mincemeat out of any gaff rigged boat and many bermudian ones. She has faultless manners and a quite unbelieveable capacity to sail herself and is a delight to live on. Anyone who has tried her finds it difficult to believe that she should so excell in so many different areas. There is no doubt that she represents a perfect, living example of all that Albert Strange stood for and describes exactly his amazing skill and understanding of the art of which he was merely an amateur practitioner. The really fearsome sum of money and the inordinate effort and attention to detail is completely rewarded and I do not think that it could have been spent on anything better, it could have easily bought an average boat in average condition twice her size.

Traduction en français :

Voici le récit écrit par Michael Burn de la restoration profonde qu’il a réalisé pour le 75eme anniversaire de Sheila. Ce texte écrit pour mémoire a été publié dans le yearbook de l’Old Gaffers Association. Il est très précieux pour l’entretien du navire et il a donc été traduit en français.

Sheila

Une confiance intacte

par Michael Burn

Pour les membres qui ont eu le courage de lire, l’année dernière, les raisons que j’ai données pour la restauration approfondie de Sheila, j’écris cette année pour raconter en détail ce qui a été fait, pourquoi, et ce que j’ai appris jusqu’à présent. C’est forcément un document long, et même incomplet, mais j’imagine qu’il est peu probable qu’un exercice de cette nature soit refait et, puisque Sheila est ce qu’elle est, je pense qu’il vaut la peine d’en faire un compte rendu. Comme tout objet ancien de valeur, elle avait naturellement été adaptée aux besoins et aux modes de l’époque comme cela devrait être le cas. Mes efforts ont cependant été dirigés vers une suppression du vernis du temps pour examiner la conception originale. Ceci en particulier pour voir si les écrits et les affirmations de Strange seraient confirmés dans la pratique, puisque les vertus qu’il revendiquait me semblaient particulièrement dignes d’être recherchées. C’est tout à l’honneur de Strange, et tout à fait à celui de Jim Wilson, que son état original soit resté en grande partie inchangé lorsque je l’ai trouvée, mais de nombreuses petites différences étaient évidentes. Depuis mes années de restauration de vielles automobiles, je sais absolument qu’il n’y a aucun intérêt à doter d’améliorations modernes une pièce d’époque; toute la saveur de l’époque est perdue et les avantages du temps ne sont pas obtenus. Ceci, je le réalise pleinement, est très sujet à controverse, mais j’ai prouvé mon point de vue avec tant de succès avec les voitures et maintenant avec Sheila que je n’ai pas peur de le maintenir. Le corollaire de ce qui précède est que non seulement les détails de l’artefact doivent être recréés exactement, mais qu’ils doivent être recréés avec les méthodes et les matériaux de l’époque. Les raisons sont la philosophie évoquée ci-dessus, auxquelles s’ajoutent des raisons très pratiques. Un mélange de techniques d’âges différents pour résoudre des problèmes de restauration souffre généralement du syndrome des “vins nouveaux dans de vieilles bouteilles”. Cet idéal n’a dérapé qu’une ou deux fois et ces dérapages n’ont aucune incidence significative sur le résultat. En outre, des points importants de la construction originale peuvent être négligés ou des problèmes majeurs nouvellement intégrés dans une restauration en ne comprenant pas mais en réutilisant une solution de conception ou de construction originale. C’est pour ces raisons que la restauration de Sheila a été si « complète » et si terriblement coûteuse. Bien de choses qui « auraient bien fait l’affaire» furent abandonnées dans une recherche impitoyable de ce que Strange avait créé exactement. Il est juste de dire également qu’étant ce qu’elle est, et que c’est son 75ème anniversaire, beaucoup de choses, bien que dans le caractère et la qualité de l’époque, ont été faites à un niveau plus élevé que ce qu’elle avait connu à l’origine, bien que le seul élément qui a vraiment coûté de l’argent ici était la construction d’un nouveau canot à clins.

Le premier exercice sérieux fut de remettre la quille. Se présentaient à moi les premiers problèmes éthiques. Devais-je remettre la pièce de remplissage de 12,5cm qui a probablement été ajoutée en 1914 pour augmenter son tirant d’eau ou devais-je reconstituer exactement telle que dessinée. Pat Walsh, qui a très certainement fait la modification, connaissait bien Strange et, très probablement, avait son accord lorsque Sheila a été reconstruite. Sur la côte est de l’Angleterre où 12,5cm sont d’une importance cruciale, ma décision a été compliquée, “laisser de côté ou remplacer”. Sanctifié par le temps, je pense que Walsh savait ce qu’il faisait. Donc elle cale maintenant 1,20m. Ensuite, devrais-je faire des efforts fantastiques pour trouver le bon acier de Lowmore et faire forger les boulons de quille ou utiliser du bon acier inoxydable approuvé par l’Amirauté. En tant qu’ingénieur, je savais que les chances de trouver du fer d’une qualité suffisamment élevée étaient très limitées et je que pouvais fabriquer des boulons parfaits selon les normes les plus élevées dans mes propres ateliers. C’est presque le seul endroit où un matériau autre que celui disponible à l’époque fut utilisé. Les boulons avaient de grandes têtes évasées et pénétraient dans le fer de la quille par des trous coniques. Ils étaient vissés sur la fonte avec de gros écrous en bronze. Des rondelles coniques épaisses en «acétal» furent placées entre le fer et l’acier pour l’isolation électrique. De l’EN58 fut utilisé pour les boulons, le seul acier inoxydable adapté au fer en conditions anaérobiques des boulons de quille et le seul véritable problème possible est avec les écrous, mais chacun est très accessible (les écrous en acier inoxydable se grippent aux boulons en acier inoxydable !) La tâche s’est déroulée à merveille et puisqu’aucune attention n’étaient requise dans les zones voisines, le chantier n°2. a été abordé avec beaucoup plus d’enthousiasme. Elle était beaucoup plus jolie avec sa quille.

L’activité suivante, que j’ai entrepris seul, était certainement la plus controversée aux yeux des amis et certainement la plus intrigante. C’était une grande grâce que cela ait été fait si tôt, sinon je n’aurais peut-être pas eu le cœur de le faire du tout. Je voulais recréer exactement le pont d’origine et comme le problème était considérable, il constituait la pierre angulaire de toute l’affaire.

Il soulignait très clairement la leçon sur le vin nouveau et les vieilles bouteilles et servait également à faire comprendre à ceux qui l’entouraient que quelque chose de légèrement différent était en cours.

Un nombre surprenant d’oiseaux de mauvais augure sont apparus à ce moment-là, la plupart des gens pensant et disant que j’étais fou. Comme tout ce avec quoi je devais travailler était une coque nue et défraîchie et des rêves, c’était un sinistre ouvrage, possible uniquement parce que le chantier m’avait donné une clé du hangar pour mon usage personnel. De nombreux samedis et dimanches après-midi étaient consacrés à racler les vieux joints de pont et à réfléchir à Albert Strange.

La raison pour laquelle il fallait faire correctement le travail était principalement structurelle, même si la philosophie et la vanité y entraient en jeu. Les ponts des yachts de cette période (et certainement celui de Sheila) étaient des structures solidaires de la coque et parler de colle marine est utiliser le terme à juste titre puisqu’il est vitalement nécessaire que les planches du pont soient collées ensemble pour former un tout structurel avec la coque. Il ne suffit pas d’appliquer simplement un produit jointoyant. La solution consistant à recouvrir le dessus du pont avec autre chose ajoute du poids et, pire encore, empêche d’isoler la source d’une fuite. L’un des grands avantages d’un pont en pose simple est que là où l’eau entre, il y a une fuite et elle est facilement stoppée. Comme tout le monde le sait, une pont traité qui fuit est pire qu’un jeu de taquin en trois dimensions. Le pont de Sheila est l’un de ces superbes ponts où les planches sont bardées et courbées avec les lattes de couverture insérée dans la feuillure. Il est donc vraiment ingénieux et s’avère être un plaisir durable pour les yeux. Les travaux ont commencé par la fabrication d’un ensemble spécial de racloirs. Cela était nécessaire puisque les rainures n’avaient qu’une largeur de 3mm et se rétrécissaient jusqu’à ce que les planches touchent. Il a fallu enlever toute trace des anciennes joints (le pont était bâché depuis 40 ans) et rétablir le bois nu sur les côtés des rainures pour que la nouvelle colle marine adhère. La colle marine Jeffries n°1 est toujours disponible. Les racloirs, après quelques tentatives, ont été fabriqués à partir de vieilles limes très soigneusement meulées dans la forme exacte de la rainure, soigneusement finies avec un bord avant tranchant et ensuite durcies. Il y avait plus de 200m de rainure et d’innombrables fixations invisibles à négocier. Le pin Kauri s’est avéré extrêmement abrasif et je suis devenu expert dans le parfait réaffûtage des angles des racloirs, sans parler des vieilles lames de scie à métaux soigneusement affûtées, nécessaires pour retirer le calfatage du fond de la rainure. J’ai dû en épuiser des dizaines seul et le temps de réalisation pour une tranche parfaitement préparée était d’environ 1,3m par heure, le tout à faire en double avec les mains et les genoux en utilisant les deux mains sur les racloirs. C’était un travail formidable et à la fin rien n’avait changé, sauf que les rainures étaient recouvertes de ruban adhésif pour empêcher d’entrer la poussière des travaux ultérieurs.

Il était prévu que les joints soient réalisés juste avant la mise à l’eau, car nous pensions que l’ensemble de la restauration prendrait encore au moins un an et demi, période pendant laquelle la coque allait sécher davantage et le les joints du pont s’ouvriraient. Si le pont devait être jointoyé plus tôt, je supposais que lorsqu’il s’ouvrirait davantage, l’espace ainsi produit exercerait une contrainte intolérable sur la colle en tension. Bien que la Jeffries No.1 soit censée être assez flexible, cela semblait créer trop d’effort. Il était prévu que le bateau passe un certain temps dans l’eau avant que les finitions afin que des travaux de cette nature ne soient pas effectués avec des joints vraiment béants.